Published in Scoop Homes & Art, Spring 2013

A culture that spend decades creatively shackled is experiencing a new revolution, with an enormous talent pool of Chinese artists finding purchase in the West.

In China, contemporary art is the product of a collective moment rather than the talent of individual artists. The death of Mao in 1976 might have signaled the end of the Cultural Revolution but it also marked the start of a creative awakening, where artists reversed the effects of the past three decades by creating explosive, emotionally charged works.

“One of the things that really sets Chinese contemporary art apart is the way it’s shaped by a very specific set of social situations which occur in China anywhere from the eighties onwards,” says Aaron Seeto, curator of the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and director of the National Association for the Visual Arts. “It’s really an art of its time but its relationship to different types of social transformation across the country is what’s most interesting to me.”

The Chinese art scene’s one-of-a-kind relationship with historical context has also shaped its progress on the international art circuit, as well as the ascension of a series of art stars who commit observations on the country’s dizzying Westernisation to installation, sculpture and ink.

Xu Zhen is a case in point. In 2009, the controversial artist, who once exhibited a leather cathedral woven out of bondage equipment at Hong Kong’s Art Basel, shelved his highly bankable public identity to form MadeIn Company – an artist’s collective intent on churning out contemporary art at a production-line pace. “Commerce and art are no longer separable in modern society,” Zhen said in a September 2012 interview with lifestyle magazine That’s Shanghai. “We don’t resist commerce. We make commerce serve art.”

Half a world away from Madein Company’s Shanghai headquarters, the White Rabbit Gallery sits on a sun-dappled Sydney street. The four-story 1920s knitting factory, home to a 700-strong contemporary Chinese art collection assembled by philanthropist Judith Neilson, will soon feature Madein Company’s Immortals Trails in a Secret Land (2012) as part of Serve the People, a biannual exhibition curated by Edmund Capon, the former director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Although the show, which unfolds over six months from September, takes curatorial cues from an old Maoist slogan, it also plays with the idea of creative production as a form of service – a theme that overturns art world hierarchies even as it informs contemporary Chinese art.

“‘Serve the people’ was, ironically, one of the catch-phrases of Mao’s Cultural Revolution – that event which cast such a dark and lingering cloud on the Chinese people and extinguished its creative spirit,” explains Capon, who first witnessed the maxim during a 1974 excursion to China. “Now I think art ‘serves the people’ in liberating their spirits and their imaginations.” This also recasts contemporary artists as service providers tasked with reviving the country’s cultural imaginary rather than creative geniuses who have actively chosen the artist’s life.

The Cultural Revolution ended in 1976 but its spectre has loomed over China’s unconscious ever since. For example, Sun Furong’s Nibbling Up Series: Tomb Figures (2008) sees a row of formless subjects cloaked in shredded Mao suits, shoulders hunched in despair. The mixed-media piece draws its power from its holes and absence, which hint at a spiritual erosion that’s proven impossible to repair. Elsewhere, Zhang Peilli’s installation Happiness (2006) is a lesson in the revolutions’ flipside. Appropriating footage from the 1975 film In the Shipyard, the piece conveys the euphoric thrills of emancipation via a montage of beaming smiles.

If contemporary art in China is a service, then it’s one that’s highly prolific. And for White Rabbit’s founder Judith Neilson, this proliferation is precisely the source of its appeal. “I am focused on Chinese contemporary art because there are more artists in China than the rest of the world,” offers Neilson, whose obsession was stoked during a chance encounter with Beijing artist Wang Zhiyuan at a Sydney art opening.

“In America there might be 100 contemporary artists, but in China there might be 100,000. And in both countries, the same proportion would be good. You would also find those interesting artists who would never make it due to lack of fortune or visibility. You could never put together a collection as large as I have on American art or Indian art. It’s impossible,” she continues.

Although the White Rabbit’s twice-yearly shows are usually curated by Neilson’s daughter Paris, the gallery’s expansive collection is the result of regular buying trips to Shanghai and Beijing, where she avoids the hype of auctions in favour of forging personal connections with up-and-coming artists.

Neilson also says that her collector’s eye isn’t as enamored with technical mastery than it is with artists who show a willingness to make mistakes. “A lot of the work is not meticulous, it’s experimental. Artists will try all kinds of strange things and aren’t afraid to fail. That’s why I like it,” she admits.

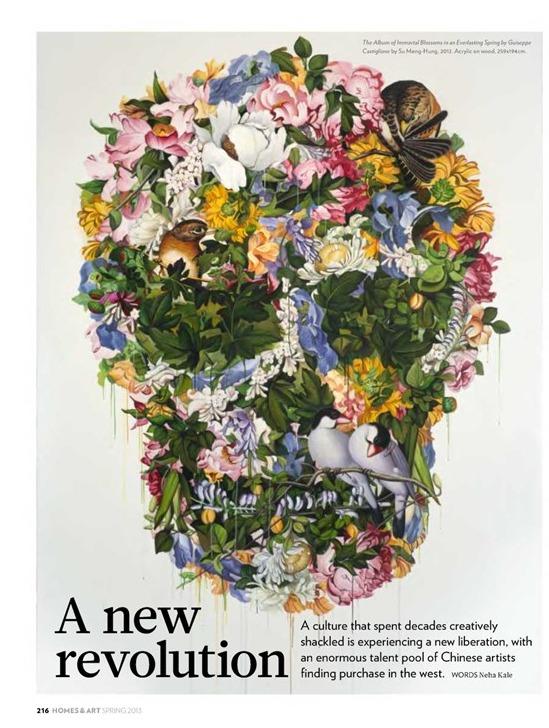

Chinese contemporary art often serves up readymade responses to the Western art market through aesthetic – and symbolic – crudeness. In Dregs of Old Society, Liu Dahong’s childlike sketches imbue Mao-era political satire with comic-book charm. And Su Meng-Hung’s The Album of Immortal Blossoms in An Everlasting Spring by Guissupe Castiglione (2002) might borrow the 18th century painter’s florid visual style but its skull motif lampoons the economics of the modern art world, in a nod to the diamond-encrusted versions made famous by Damien Hirst. In this case, pandering to the art world itself becomes a form of cultural service – success stems from the ability to pander to broadcast the version of China that consumers most want to see.

“[The contemporary art scene] in China is like a restaurant in Chinatown that sells all the standard dishes, such as kung pao chicken and sweet and sour pork,” writes Ai Weiwei, the political provocateur who’s widely considered China’s most famous living artist. “People will eat it and say it is Chinese, but it is simply a consumerist offering, providing little in the way of a genuine experience of life in China today.”

Whether or not you side with Weiwei, he overlooks the way Chinese artists serve global forces while fulfilling local missives – shaking up the way we perceive contemporary art in the process.

“There are 300 Chinese artists in the White Rabbit Collection but these are just the ones I like,” says Neilson. “You could go to China and find hundreds more. And I have no idea if they’re the best, or the worst, or whether they will last. Only history will tell us that.”