First published in SPECTRUM, The Sydney Morning Herald, May 2019.

Arthur Jafa remembers the first time that art imploded the way he saw the world. The artist and cinematographer, 58, has spent the last 30 years making moving images that capture the African-American experience — a vast and complex universe that exists beyond the narrow lens of mainstream culture. When he was growing up in Tupelo, Mississippi, he came across the work of Jack Kirby, the comics creator behind Fantastic Four and Captain America. Kirby’s vision would stay with him forever.

“[As a child] I didn’t realise that people made movies, but I was very aware of Jack Kirby,” he says, the flattened consonants particular to his adopted hometown, Los Angeles, mingling with a Southern drawl. “Kirby was the single greatest force at Marvel Comics, someone who was functioning at a certain level of creativity and virtuosity.” He grins. “Kirby was the beginning of my sense of what it means to be an artist. Someone whose shit is doper than anyone else’s, whose work has more energy and pizzazz.”

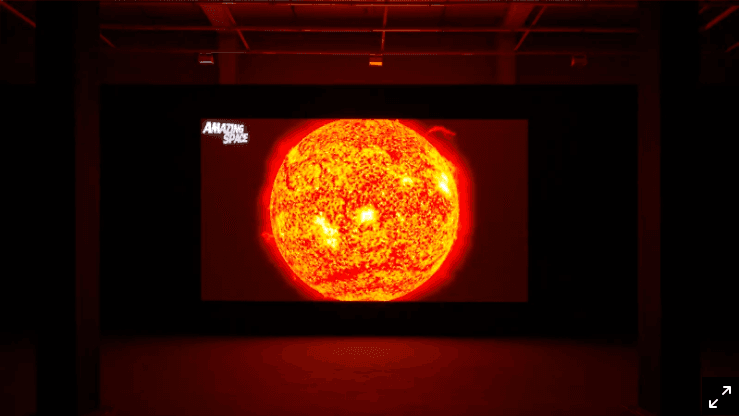

Jafa — good friends call him AJ — is sitting on a leather couch inside a sun-washed office at the National Art School. An hour from now, the Biennale of Sydney will announce the artists that will exhibit in 2020. Jafa is part of the selection, along with the Pakistani-American sculptor Huma Bhabha and South African photographer Zanele Muholi. Outside, the school’s sandstone grounds practically thrum with electricity. Jafa, who’s wearing baggy, blue jeans and a small, silver bolt through his right eyebrow, is unfazed. In May, the artist will return to Australia to screen Love is the Message, the Message is Death as part of the new The Hidden Pulse series at Vivid Sydney. The 2016 video installation intersperses images of African-American greatness (Nina Simone! Obama! Biggie!) with footage of the violence levelled at black bodies through history to the rhythm of Kanye West’s rap-gospel anthem Ultralight Beam.

Love is the Message has been shown everywhere from Sant’ Andrea de Scaphis in Rome to the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston and turned Jafa into a reluctant art-world celebrity. But never mind the accolades. The work’s true import is visceral and personal. It compresses, over seven transcendent minutes, all the joy and pain of the black experience. It bends space and time and splices past and present the same way the pioneering African-American DJ Larry Levan — one of Jafa’s touchstones — dropped the soul tracks he grew up with at 1970s nightclub Paradise Garage. Or later, modern hip-hop greats such as Kendrick Lamar would sample the funk legends that ruled the same era. For Jafa, music has always been the truest expression of identity.

“I think black music is bound up with what it means existentially to be a black person, and this was mapped out before I was born,” says Jafa, who has the kind of rare intellectual swagger that’s validated nearly every time he speaks. “I’ve always said that I want to make cinema with the power and beauty of black music. [Black music] comes from one of the oldest and richest musical cultures. In a paradoxical way, when African people were enslaved and brought to the US and their mobility was radically circumscribed, a thousand-year-old musical tradition that had been tethered by the ruling class was untethered.”

He rakes a hand through his salt-and-pepper braids.

“Our super power is this precise ability to make culture in freefall — outside of the normal things that reinforce our sense of ourselves as a community, such as land.”

*

Jafa was born Arthur Jafa Fielder in 1960. Growing up in Tupelo, a small city known as the birthplace of Elvis Presley, he consumed comics, of course. Also, movies and television. “I didn’t grow up looking at Picasso,” he laughs. “I watched TV series like Gilligan’s Island and creature features such as Night of the Living Dead. I [remember] seeing Eight and a Half by Fellini and thinking ‘what is this?!’ The sex scenes, the cutting away — it was surreal, totally operating outside any frames.”

Jafa went on to study architecture at the elite, historically black college Howard University in the early ‘80s. There, he started thinking seriously about aesthetics and the relationship between form and content. “I’d ask myself, if Electric Ladyland was a house, what would it look like?” But images still compelled him. He moved to Atlanta following graduation, taking odd jobs while establishing himself as a cinematographer. In 1989, his breakthrough came in the shape of Daughters of the Dust. The landmark film, which revolves around the women of the Gullah community, an African-American culture that’s existed for centuries on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina was made by Jafa’s then-wife Julie Dash and art-directed by the acclaimed contemporary painter Kerry James Marshall. The first major release by a black, female director, Daughters of the Dust would later inspire Beyoncé’s iconic 2016 visual album Lemonade.

On Daughters, Jafa’s camera renders the film’s black matriarchs and their tropical home with a lushness and empathy that would become his visual signature. You see it on films such as Spike Lee’s Crooklyn, a 1991 comedy-drama that follows an African-American family living in a candy-coloured Bed-Stuy in the early ‘70s and, more recently, on Cranes in the Sky and Don’t Touch My Hair, the Technicolour music videos he shot for Solange’s 2016 opus A Seat at the Table.

“People still talk and think about Daughters, but it was Julie’s composition and Kerry and I were just the musicians,” he says, with a wry smile. “Some people stay in other people’s bands forever and other people start their own bands.”

For Jafa, starting his own band meant fleeing to the art world, where creative autonomy was guaranteed — at least on paper.

“I could never garner the support for the things I was interested in so in the nineties, I said ‘I’m going to do the art thing’ and I had quick success,” says Jafa, whose first piece was shown as part of a 1999 show at New York gallery Artists Space and who caught the eye of superstar curator Hans Ulrich Obrist following a travelling show called Mirror’s Edge. “After a year, I was in the Whitney Biennale but after a three-year period, I became super disenchanted with the art world.” He sighs. “I can’t tell you how many times I was at parties and was the only black person in the room. It wore me down. It was exhausting.”

*

By now, Arthur Jafa’s art-world comeback has become the stuff of legend. The story goes that Jafa, living in L.A. and working once again as a cinematographer was invited to participate in Made in L.A, a 2016 biennial. He showed three-ring binders of found images of black culture, references he’d been collecting over his lifetime. He started thinking about how a montage of moving images could reflect a black aesthetic, an expression informed by beauty and violence, promise and failure. In three hours, he edited together clips of black icons and artists, Martin Luther King speaking, Hendrix performing. He added home videos of black life — his daughter’s wedding, teenagers freestyling. Next, clips of police violence, the 1991 Rodney King shooting, a Texan woman pulled up on the street. The track’s gospel chords and frenzied raps gave the piece an epic, urgent structure, music dancing with visuals, resonances between images building to crescendo again and again.

He was about to put it on Youtube, but instead gave it to his friend, filmmaker, Khalil Joseph, who showed it during an early preview of Lemonade, which he was directing for Beyoncé. It floored viewers, moving people to tears. In the audience was the legendary New York gallerist Gavin Brown who signed Jafa to his stable and gave the artist his first solo show in over ten years.

A few days after the work’s first New York screening, Trump was elected. But Jafa is less interested in pandering to white, liberal handwringing than he is in addressing African-American subjects and portraying blackness in all its richness and nuance — part of a lineage that goes back at least to the great 1960s artist Roy DeCarava the first photographer to properly light black skin.

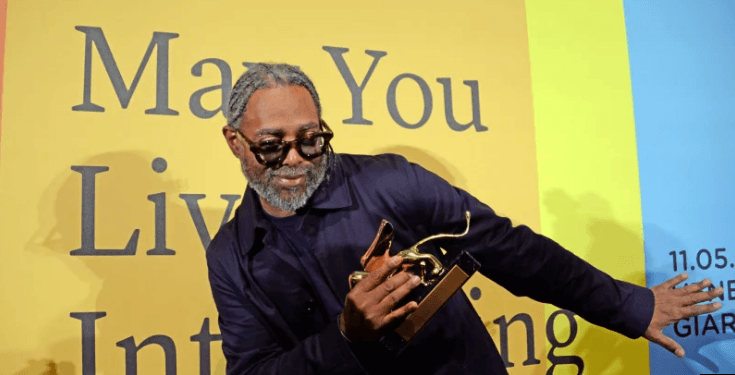

“All my white friends were freaked out when Trump got elected, but the black people I knew were not freaked out — Black Lives Matter arose under Obama’s eight years, let’s be for real,” says Jafa who directed Jay-Z’s video 4:44 and will take part in the 58th Venice Biennale later this year. “I thought black people would be struck by Love is the Message but I could never have anticipated the universal response people had to it. Non-white people have a muscle that lets us understand art by white people and get what’s at stake. But white people don’t get a chance to exercise that muscle because they’re used to everything being centred on them.”

Lately, Jafa has been using his long-overdue platform to explore this dynamic. The White Album, a video work that screened last year at California’s Berkeley Art Museum nods to white icons such as The Beatles and Joan Didion. It sends an eerie hologram of Iggy Pop wandering through a montage that includes Dylann Roof and Dixon White, a converted racist who became a viral sensation after ranting online about the dangers of white privilege.

“It’s my attempt to embody the tension between ‘bad’ whiteness or white supremacy and the white people that I love and cherish,” he says. “It’s like the way women need to have a robust understanding of patriarchy, whether they are feminist or not.”

But for Jafa, whose 2018 show Air Above Mountains, Unknown Pleasures featured a staged photograph called La Scala which see the artist dressed up as Mary Jones, a trans, black pickpocket and sex worker who lived in 1830s Manhattan, this process is just as much about resistance as it is about understanding.

“[My art] is about refusal,” he says. “People experience this as an affront because it discombobulates them. But I’m not going to decentre blackness in my work.”