First published in Open Skies magazine, May 2014.

Neha Kale meets the people running historic independent movie theatres in Sydney, San Francisco, Paris, Rio De Janeiro, Bangkok, London and Mumbai, who all believe that movies are best enjoyed on the big screen.

Thomas Edison was the original overachiever. In 1894, the fabled inventor, best known for conceiving the electric light-bulb, patented the Kinetoscope – a device that allowed viewers to experience moving images through a peep-hole – before showing travel scenes and celebrity footage to spellbound audiences at a music hall in New York.

Over 200 years later, the words “Picturehouse” – spelled out in cool blue neon – mark out an unassuming facade on a sun-dappled Sydney street. The sign may lure passers-by into the former Paramount Pictures building but it also signals the power of celluloid magic, a force that’s grown beyond Edison’s makeshift cinema to overcome the limits of technology, distance and place.

“These days, you can watch whatever you want very cheap or free from your home,” says Barrie Barton, the co-owner of the Golden Age Cinema, the velvet-lined theatrette housed in the building’s basement that in every way lives up to the promise of the sign. “But what’s missing is the experiences that exist around watching a movie. Film has always been about so much more than what’s happening on the screen.”

Barton isn’t alone in this theory. The Golden Age, which invites patrons to sip flawless Americanos while watching everything from sixties thrillers to Sophia Coppola’s newest offering, is only one example of the global resurgence of the old-fashioned picturehouse. It’s also evidence that the enduring pleasures of a night at the movies could be enough to surrender our Netflix addiction – 44 million subscriptions and rising at last count.

Social researcher Mark McCrindle believes that independent cinemas increase the chances of stumbling upon a film that speaks to you, much like unearthing hard-to-find vinyl at a record store or a dusty paperback that goes on to become a personal classic. “Independent and arthouse theatres allow people to “discover” a movie and share their recommendation with friends, an approach that’s different from the mass distribution associated with watching movies online,” he explains.

For Dr Lisa Ethridge, Senior Lecturer in Media and Communication at RMIT University, sitting with a laptop in the dark can’t compete with the joys of being part of an audience. “Independent theatres continue the tradition of the cinema as gathering place where people can meet to talk over ideas relating to the film,” she explains. “They let viewers share a space together, laugh, wonder, form a collective mind and share a collective dream.”

Dotted everywhere from the backstreets of Paris to Bangkok’s electric Siam Square, these one-of-a-kind picturehouses prove that this collective dream is alive and well.

Golden Age Cinema, Sydney

If there’s a fine line between the sentimental and nostalgic, then the Golden Age navigates it with aplomb. The 55-seat basement cinema might be based in a heritage-listed building that was once the epicentre of Australia’s film industry but it’s less interested in recreating the past than is in showing Sydney cinephiles how old-fashioned rituals can deepen modern-day film appreciation. “We wanted to create something for a modern audience that stayed true to historical DNA while avoiding cliches,” says Barton, who established the Golden Age in 2013 and whose previous ventures have included Rooftop Cinema, a venue that combines open-air movies with 360-degree views of the Melbourne skyline. “We knew that it was something we had to tackle through design.”

Together with his brother Robert and a local cast of interior designers and furniture makers, Barton set about re-imagining the theatrette, a dusty space that hadn’t been used since 1971, by installing antique theatre chairs from Zurich and building a moody, thirties-inspired bar that’s the perfect backdrop for an anticipatory cocktail or post-film discussion. Barton maintains that the bar – which offers buttery leather banquettes and salted caramel sundaes – was the element of the Golden Age that was hardest to get right. “The bar is really beautiful and brand new but feels like it was always part of the building. That was the hardest thing to achieve creatively,” he says.

However, the Golden Age’s focus on reacquainting audiences with the thrills of an evening at the pictures isn’t limited to the pleasures of a pre-movie drink – it also invites viewers to buy tickets to classics such as American Graffiti and Creature from the Black Lagoon at original, pre-inflation prices.

Address: Paramount House, 80 Commonwealth Street, Surry Hills, Sydney

Roxie Theater, San Francisco

Most of us have the kind of friend with a knack for unearthing obscure, mind-bending movies but for those of us that don’t, there’s always the Roxie. A longtime fixture of San Francisco’s graffiti-etched Mission District, the freewheeling picturehouse, which was founded by a disgraced watchmaker in 1909 and screened adult films in the late sixties, is a lesson in the art of cult. “We like to screen the coolest, weirdest stuff from the past, present and future,” laughs Mike Keegan, the Roxie’s programming director. “Since every movie you’ve ever wanted to see is basically available for free online, we want to make you feel like you’re going to the house of a friend who knows you and wants to show you something cool that they think you will like.”

Although the Roxie’s shoestring selection of cinema treats is limited to candy, soda and popcorn, when it comes to audacious programming, the theatre punches above its weight. The cinema, which regularly hosts discussion panels and Q&A sessions with filmmakers, screened the world’s first film noir retrospective and early work by indie wunderkinds Joe Swanberg and Alex Ross Perry along with arthouse gems such as Danish crime drama Drive.

Keegan, who’s a fan of old films that reflect a certain time and place, says that inventive cinema is only one element of a memorable Roxie screening. The theatre is equally notorious for parties and events that bring the city’s film community together and speak to the zeitgeist.

“In a couple of weeks we’re showing the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in 35 mm, a documentary about outlaw motorcyclists in Baltimore and some Wes Anderson movies, with all-you-can-eat pizza,” Keegan says. “We once Skyped Roman Polanski from Paris during a screening. Ten years from now, there may only be a couple of cinemas in every city – an old movie palace, a nice multiplex and hopefully a scrappy, seat-of-our-pants organisation like us.”

Address: 3117 16th St, San Francisco, California

La Pagode, Paris

Unfolding on the banks of the River Gauche and lined with candlelit bistros, pocket-sized florists and Eiffel Tower vistas, Paris’ seventh arrondissement is an exercise in Gallic fantasy. However, nothing sums up the neighbourhood’s ability to transport you to another realm quite like La Pagode, a Japanese-inspired cinema that was built by the director of the city’s Bon Marche department store as a gift for his wife in 1895. The movie theatre, which features gilt dragon sculptures, intricate ceiling frescos and red velvet seating, also represents an Asian spin on the typical Parisian arthouse – although it screened early works by French New Wave masters such as Jean Cocteau in the sixties it also host premieres by directors visiting from Japan.

“We regularly feature Japanese cinema along with films by arthouse directors such as Pedro Almodóvar and David Cronenberg,” explains Marie Durand, director of events and partnerships at Etoile Cinemas, La Pagode’s operator. “And we also premiere local films such as Les garçons et Guillaume, à table!, which stars French theatre actor Guillaume Gallienne.”

But a history of championing some of the world’s most celebrated filmmakers is only one explanation for La Pagode’s role in Paris screen culture – Durand says that the cinema regularly holds masterclasses with directors such as Robert Bresson along with a cinema club that includes movies and debates based on important cultural moments. Tired of the intellectual stimulation? You can always sip rose tea in the theatre’s miniature Oriental garden.

For Durand, La Pagode’s silver screen credentials come second to the sense of escape promised by the cinema’s Japanese Room – an otherworldly viewing space adorned with chandeliers, stained glass windows and tapestries.

“Every time you visit the Japanese Room, you can’t help but marvel at a new detail – whether it’s a new animal on a painting on the wall or a sculpture near the door,” Durand offers. “Even if you’ve been visiting the cinema for ten years, it takes you by surprise every time.”

Address: 57 Bis Rue de Babylone, Paris, France

Cine Joia, Rio De Janeiro

On Rio’s Copacabana beach, where an endless expanse of white sand has given way to faceless hotel chains and a rainbow of sun-worshippers, tourism risks eroding the precinct’s status as hub for the city’s cultural life. Luckily, Cine Joia, a rebellious picturehouse intent on celebrating the city’s film culture, has made it its business to keep the beachfront’s creative energy alive.

Although Raphael Aguinaga – the filmmaker and entrepreneur responsible for restoring the colourful 1960s cinema in 2011 – is passionate about screening Brazilian and international independent films, opening the 87-seat theatre up to other kinds of performances is also part of his mission.

“As the oldest operating street theater in activity in Rio and we are known for high quality in our programming but we also believe in hosting other forms of artistic expression such as poetry, music and drama in our space,” he says.

This means that a typical week at Cine Joia could include a free screening of the De Niro classic Taxi Driver, the premiere of Brazilian documentary Trampolin du Fort or a night of slam poetry. The theatre also champions Rio’s cultural events – in 2013, it aired a series of films exploring inner-city graffiti culture to coincide with the city’s annual Urban Art Fair and it plans to acquaint Brazilian audiences with the work of eight Middle Eastern filmmakers by hosting the Arab Film Festival this year.

Cine Joia, which involves its audiences in a bi-monthly fanzine that celebrates local film culture, is equally intent on shaping the next generation of film enthusiasts.

“Education is a really big issue in Brazil. We believe that movie theatres can also serve as classrooms and we often screen documentaries to student groups in the morning,” Aguinaga says. “We’re a small theatre with big ambitions.”

Address: Avenida Nossa Senhora de Copacabana, 680 Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro

Scala Cinema, Bangkok

Navigating the five-minute journey between the Siam BTS station and the Scala, a lavish picturehouse that was established in 1969, calls for an aversion to everything that makes Bangkok intoxicating: throngs of people, bustling street vendors and an endless sea of neon. But stepping inside the marble foyer, a space characterised by soaring ceilings, giant bronze flowers and a staircase that seems to float in mid-air, is proof of the Thai capital’s tranquil second face.

“The Scala’s architecture is a combination between East and West and represents a harmony between two different worlds,” says Suchart Vudthivichai, the cinema’s long-time creative consultant. Vudthivichai works closely with proprietor Nanta Tansacha, whose stage actor father Pisit Tansacha built the 1,000-seat picturehouse – a perfect union of Thai modernism and tropical art deco – during the cinema construction boom that swept the country during the sixties.

Although it’s been nearly half a century since Tansacha doled out ice-cream to Friday night moviegoers, the Scala’s original spirit has remained intact – an attendant manning a wood-panelled booth jots down your seat number on a ticket stub and a grinning usher, wearing a lemon-yellow tuxedo, makes sure you find your seat. The fact that you can purchase a ticket and box of popcorn for around 130 baht nods to a pricing approach that’s as insistently retro as the decor.

However, the Scala, which swapped its 35mm projector for a state-of-the-art digital system in 2013, is fiercely committed to pleasing modern-day audiences.

“We screen a wide variety of movies and relentlessly search for good art films and fine documentaries along with first-run studio films, Oscar and Golden Globe winners,” explains Vudthivichai.

For Tansacha, the threat that this silver screen oasis may be demolished, is no match for the faith in her family’s legacy or the loyalty of her staff many of whom have worked with her since the seventies.

“Our family has been in the entertainment business since my birth and movies are our heart and soul,” she says.

Address: Soi 1, Rama I Road, Siam Square Bangkok

The Phoenix, London

Perched on an unremarkable high street in northwest London, the Phoenix Cinema is a real-world testament to British film history. The elegant single-screen cinema, which also happens to be the United Kingdom’s oldest purpose-built movie theatre, has played host to everything from silent films set to live music and 1920s jazz movies to cult seventies films such as Easy Rider, screened via a hulking two-reel projector. It’s 255-seat auditorium also doubled as a refuge for locals during the London Blitz.

“The Phoenix was built in 1910 and in 2010, we completed a major centenary restoration project where everything was restored to its original beauty,” says Elizabeth Taylor-Mead, the cinema’s executive director. “The walls display incredible murals and instead of wide seats with cupholders, we have old-fashioned seating in keeping with the style of the cinema. That’s what makes it unique.”

However, that’s not the Phoenix’s only unusual feature. The cinema steers clear of the surly customer service that’s sometimes associated with multiplexes and prides itself on employing staff with a personal investment in the picturehouse’s future.

“Our staff are all artists passionate about the part independent cinema plays in the community,” she explains. “If you’re standing in line to buy your ticket, they’re happy to talk to you about the film. It makes for a warm and intimate atmosphere.”

The Phoenix also extends its focus beyond its regular attendees, working with local schools, holding special workshops and running a program for people with autism.

“We really believe that film is the most democratic of all the arts,” she says. “If you look at the history of cinema, it brought together people who didn’t speak the language, who were in a difficult economic situation or were trying to figure out what they were doing with their lives. It was a way reflecting the reality of the life they were living.”

Address: 52 High Rd, East Finchley, London

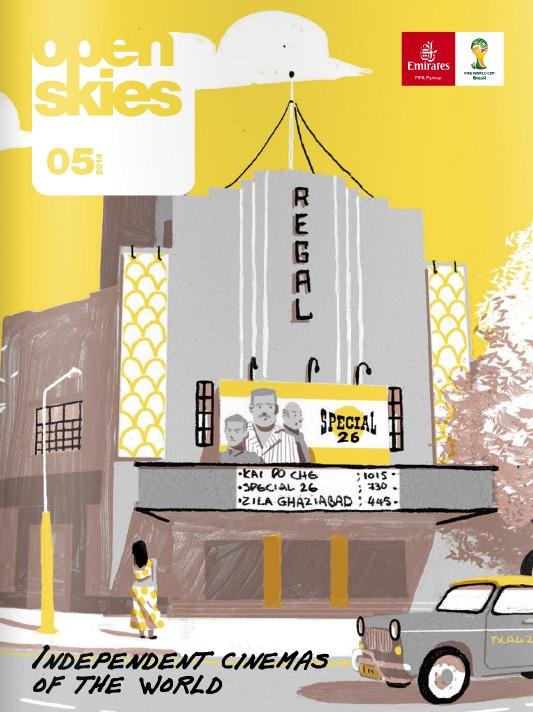

Regal Cinema, Mumbai

In Mumbai’s sepia-toned Colaba Causeway, where crumbling architecture shares sidewalk space with billboards advertising the latest broadband plan, it’s difficult to distinguish signs of modernity from the faded grandeur of a colonial past. But the Regal Cinema – an art deco picturehouse that attracted British aristocrats in the thirties and whose clientele includes the expats, students and artists that make up Mumbai’s rising creative class – signals the ways in which the city’s history has paved the way for its current evolution.

“The Regal Cinema was the first air-conditioned theatre in Asia and also one of the first places you could watch English-language films,” says Rafique Bagdhadi, a well-known Mumbai film critic and local historian. “You booked your ticket a week in advance and when you visited it was like you were going see Hamlet at the theatre. It felt like it was an event.”

However, this sense of occasion was sparked just as much by the Regal’s refreshments as it was by the movie hall’s opulent interior, which includes a mirror-lined lobby and a main auditorium accented with orange and jade sunbursts courtesy of Czech artist Karl Schara. “There were soda fountains, vendors selling samosas, sandwiches and chai and there would always be music playing in the background,” Baghdadi recalls. “You paid your money and you always felt like it was worth going there.”

These days, the Regal – which aired the first Laurel and Hardy film in 1933 – shows a mix of English and Hindi films, from large first-run features to Bollywood fare but Baghdadi fears that this isn’t enough for local audiences.

“Once upon a time, a single-screen cinema would run a film for one or two weeks but multiplexes changed the whole way of looking at cinema,” he says. “The Regal still stands but it’s not quite what it used to be.”

Address: Cecil Court, Colaba Causeway, Apollo pier, Colaba, Mumbai,