First published in VAULT magazine, February 2016.

Laden with pastiche, symbols and signifiers, the work of shapeshifting British artist Grayson Perry transports us to the edge of self-awareness while preventing us from plumbing its darkness and depths.

There are two Grayson Perrys. The first makes ceramic pots, tapestries and etchings that wrap winking takedowns of gender, class and British identity in a package once reserved for suburban housewives; parlays a traumatic childhood in working-class Essex into a BBC Reith Lecture series delivered in plainspoken, electrifying language; and embraces Claire, a female persona who proves that feminine, domestic traditions count at least as much as balls and bombast when it comes to contemporary art. The second creates formally unimaginative pieces that rely on rote observations, borrows from African textiles and 19th century Japanese pottery while boldly renouncing context and distances himself from art world theatrics, clad in a bright-blue nappy. Your willingness to celebrate provocateurs over populists will determine the Grayson Perry you see.

“I haven’t got a strategy!” the real Grayson Perry tells me, with the type of soul-deep, gravelly guffaw that makes you want to snort with laughter yourself. “I’ve achieved a lot of my ambitions and have been very lucky. My British Museum show was a big ambition; I built a house in Essex, which was another ambition of mine. My TV series have been really fun – but I didn’t plan to do them. A lot of my work is a case of post-rationalisation. I’d already made something and then later asked myself, ‘what was I trying to do when I made this?’ My first exhibition happened close to Christmas, so I wanted to make things that people would buy as presents. That idea seemed to have a frisson in the art world, which was all about art for arts sake. I’ve always been drawn to the idea of making things that are accessible, covetable and feminised. These things felt like they had a charge around them.”

I’m talking to 54-year-old Perry, who’s the picture of studied eccentricity complete with Mad Scientist hair and purple slacks held up by suspenders, at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, on the eve of My Pretty Little Art Career, his first major survey in the Southern Hemisphere and his biggest retrospective to date. Upstairs, journalists pore over whimsical sketchbooks, stand dumbfounded in front of giant tapestries and mill around the ceramic vases, decorated with scratchy war scenes, surprise acts of fellatio and collaged council estates, which sealed his celebrity and landed him the 2003 Turner Prize. Spending time with the 60 artworks feels like tumbling headfirst into Perry’s consciousness. “I expect that a lot of people here won’t have seen my work before and I hope that they’re engulfed by the sensual aspect of it,” he grins, betraying that elliptical way of speaking that’s peculiarly and endearingly British. “And if they don’t like it, well, I’ve tried my best!”

Perry was born in Chelmsford, Essex, a place that’s become the punchline of English class warfare, in 1960 and grew up with a violent stepfather and mother who ran off with the milkman when he was four (“I have an intense allergy to cliches,” he writes in his 2014 book Playing to the Gallery, based on his popular Reith lecture of the same name.) At 12, he started dressing up in his sister’s clothes, moved in with his father’s family as a 15-year-old, only to be rejected after he was discovered wearing Claire’s hyper-feminine dresses to go out with friends. “I was going to join the army to until I was 16 but my art teacher suggested that I join art school,” quips Perry, who’s working on a new BBC series on masculinity. “I always enjoyed doing art but didn’t really consider it as a career because I never knew what an artist did.” Perry attended Portsmouth College of Art and relocated to a squat in Camden in 1983, briefly sharing quarters with Boy George and Stephen Jones and frequenting The Blitz, the famous New Romantic nightclub where gender fluidity and flamboyant self-expression was a cause for celebration rather than concern. He also took up evening pottery classes, showing his first-ever plate Kinky Sex (1983) – inscribed with a garish crucifixion that’s confronting even thirty years later – with Chelsea’s James Birch Gallery in 1984.

“When I first came to London, I hung out with a group of young people who were all filmmakers and performance artists and they taught me not to buy into those myths about being an artist, to laugh at cool people and that being naff could be a creative impulse, that it could be okay,” explains Perry, who is married to the London psychotherapist Phillipa Perry and whose first brush with Henry Darger, the American outsider artist who suffered abuse in an orphanage and produced monumental watercolours starring hermaphrodite children, helped galvanise his own work. “Coolness is an orthodoxy and when you’re young it’s very easy to think it’s the thing to be.” That guttural laugh again. “But everybody is a rebel love! That’s just what everyone does.”

Sometimes, Perry’s status as a self-styled outsider and public aversion to conformity feel less like biographical happenstance and more like a force calibrated to cement his authority as a cultural observer and give his work the ring of truth. The Rosetta Vase (2011), a blue-and-yellow earthenware pot inscribed with intricate illustrations and sly aphorisms (“iconic brand”; “museum as cathedral”; “hold your beliefs”; “Facebook generation”) reframes historical artifact to knowingly invoke the cultural soupiness and vacant hero worship typical of late capitalism. Like all his pots, the piece – which takes cues from Japanese Satsuma pottery, an 18th century form decorated with lavish landscapes and produced cheaply for Western markets – collapses the boundaries between art and artisanal and skirts the perimeter of luxury and junk.

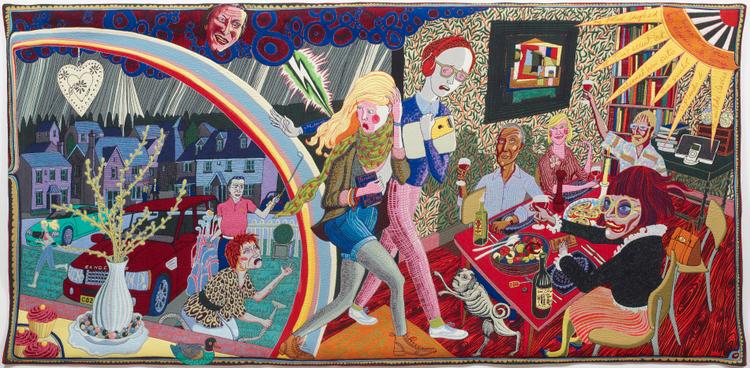

Elsewhere, The Vanity of Small Differences, a series of tapestries that follows a character called Tom Rakewell from an unashamedly tacky suburban home to trophy wife and car crash via a middle-class purgatory complete with organic carrots and Penguin Classics coffee mugs dazzles and nauseates by unspooling the ways class anxiety masquerades as good taste. These tapestries, which are woven on a mechanical loom and are based on William Hogarth’s 1732 painting The Rake’s Progress, also hint that the pleasures of Grayson Perry are less about his artistry than the “me too!” moments he elicits. His output can feel like a Where’s Wally? for our hidden delusions and secret shames.

“I’m interested in an anthropological view of who we are in every culture and I’m British so that’s what I know,” explains Perry, whose 2011 British Museum exhibition Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman cast his own work alongside objects made by anonymous craftspeople through history and who built the wildly popular A House For Essex, an ode to a fictional working-class character called Julie in 2015. “When we inherit the culture, we stick emotions to it because we’ve got feelings that are positive and negative that are part of our lives. But I’m very fond of some things about Britishness that seem daft. It’s a kind of self-examination. My schtick has always been man hours, detail and labour but as an artist you also have to learn thinking skills. It’s not about just being able to make something. You have to make something well.”

But although Perry, who was rightly criticised for suggesting that indigenous artist “borrow” from the status of contemporary art earlier this year (a gaffe that for the record, he’s sincerely apologised) insists that he’s a “postmodern potter”, pulling from a grab-bag of influences, his brand of self-examination is selective when it comes to social and historical currents. It also recalls the rather old-fashioned idea that sees the primacy of the artist’s vision supersede the work itself. While Perry’s self-portrait A Map of Days (2013), an ink-blue etching that borrows the lexicon of 17th century cartographers to trace the trials of modern-day manhood via exquisite drawings and phrases such as “Sad Puberty,” “Internet Porn” and “Lingering Doubt” proves that this approach can be poignant and powerful, works such as Claire at the Tate Gallery (1999) – in which Claire, dressed as Camilla Parker Bowles, brandishes a placard screaming “No More Art” – feels interesting mostly because of the way the artist’s life story works as subtext.

But perhaps Perry’s greatest trick isn’t his ability to make postmodern pottery or lavish tapestries but his ability to convince us that populists can shake up the establishment and provocateurs can provoke comfort rather than resistance and open our eyes to hypocrisy – while saving us from the freefall of dissolving the status quo. “People say I’m a performance artist but no, I’m a just a tranny and an artist, even if the two sometimes overlap,” Perry chuckles. “I’m glad if some young guy wants to put on dresses finds confidence by seeing me out there in the world but I don’t see myself as part of that trans-rights campaign that’s prominent on the Internet right now.. If you’re erotically motivated to put on women’s clothes, then everything else is easy.” He grins, blue eyes huge, and I’m struck by how hard it is to dislike him. “But me? I’m just getting on with what I’m doing.”

Grayson Perry: My Pretty Little Art Career shows at the MCA until May 1, 2016.

mca.com.au