First published in VAULT, Issue 18.

Kristin Olson just reminded me that the pseudonym, that cloak usually reserved for reporters that morph into superheroes in phone booths, could be useful for those of us whose biographical particulars are always slightly shrouded in doubt. The San Francisco artist, who goes by the moniker Koak (KO-AK) says that her work is the result of the dissonance she experiences on a daily basis. No wonder her paintings of naked women, limbs contorting and distending as if they were made from rubber, seem like they’re battling a villain from a comic book — one that’s lodged itself inside their bodies and refuses to leave.

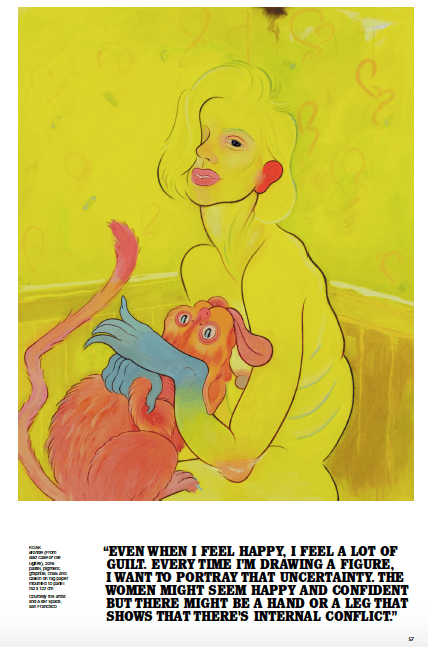

“There’s this really interesting quote from The Punk Singer, the documentary about Kathleen Hanna from Bikini Kill when she says that even when women tell our own stories about what we’ve had to deal with throughout our lives it sounds completely absurd,” laughs Koak, who has huge, blue-green eyes that go from smiling to serious in a heartbeat and whose distinct cadence, those slightly hollowed-out vowels, speak less of California than the Midwest, where she was born. “It reminds me of the way I don’t feel certain about a lot of things. Even when I feel happy, I feel a lot of guilt. Every time I’m drawing a figure, I want to portray that uncertainty. The women might seem happy and confident but there might be a hand or a leg that shows that there’s internal conflict.”

Koak was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan to artistic parents. “My dad writes code but is also a musician and my mum always wanted to paint even though she never actually did,” she grins. Like so many children who endure bouts of sickness, she found solace in comics, painstakingly drawing and re-drawing the characters she read about in X-Men. When she was a teenager, her family relocated to Santa Cruz, California, where a utopian history — communes have long proliferated in the nearby Santa Cruz Mountains — was shot through with darker currents. “A lot of my friends had tried heroin, they’d gone through really difficult things and a lot of the stuff I was making was autobiographical and personal,” she recalls matter-of-factly. Katie Harper, her high school art teacher (“she was really strange; she kept a horse skull on her desk and would show us alien autopsy videos”) encouraged her artistic abilities.

Art school, however, proved less affirming. “I went to CalArts for a year and hated it. It’s apparently a very prestigious school but it supported the idea of an artist as being kind of a party-er and the work was second to the lifestyle.” Something gelled four years later when she moved to San Francisco and enrolled at California College of the Arts with now-husband Kevin Krueger. The pair went on to set up Alter Space, a contemporary art gallery in a former bondage shop in the city’s South of Market district. “When I went back to CCA, I started doing really different work and started working on a comic book, Sick Bed Blues, which was [a big departure] from the fine art I had been doing,” says Koak, who’s just completed her Master of Fine Arts in comics. Of course, San Francisco, once home to the punk novelist Kathy Acker and the publisher Gary Arlington, who established the country’s first comic book store in the Mission has always championed the underground elements of visual culture. But as Koak points out, there’s still the question of artistic legitimacy, even though it’s been decades since Pop Art conflated the highbrow with the lowbrow.

“I recently saw a Roy Liechtenstein show and there was a painting that incorporated a reference from a famous comic book artist and the caption just said, ‘pulled from a comic book artist,”’ she grimaces, pushing aside her auburn bangs. “Literature and art are two amazing things that are so respected but comics get such a bad rap!” Not, it pays to remember, that this is entirely unwarranted. “Ulli Lust is an amazing female graphic novelist but I also really love the comic artist Brett Evans and Dash Shaw who wrote Bottomless Belly Button and Bodyworld,” she says, adding that showing alongside the cult filmmaker Mike Kuchar in August 2016 was among the highlights of her career. “My first boyfriend had a comic book collection that he gave me when we broke up, probably from guilt because he was in prison. My favourite comic books, those that use the form best, are the same old stories about older guys and younger women. It bothers me so much!”

For ten years, Koak drew nothing but intricately etched animals, rabbits and foxes with human faces (a hand-drawn animation of a deviant kitten recently made an appearance in Kitty, a short film debut by Chloe Sevigny ) but a year and half ago she returned to the human figures that she’d sketched compulsively as a child. In That Time of The Month (December), part of The Noodies, a year-long collaboration with Alter Space, a model sits on a stool cigarette dangling from her mouth, right arm pinned around her head as if by an invisible force. The lines are taut, stretched to their limit. This muse isn’t a passive object, content to bask in the artist’s gaze. Her beauty curdles into something darker, closer to what the writer Mary Russo calls the female grotesque. The same goes for Ramona’s Smize (2016), shown as part of Los Angeles group show called The Weeping Line. Close your eyes and you’ll see Picasso’s lovers Olga Khoklova or Dora Maar, open them and Ramona glares back, defiant. History tricks us, the same way paintings can.

Hello Darkness (2017), shown as part of Los Angeles Contemporary 2016, sees a naked girl with a face out of an Archie comic staring into a mirror, arms and legs playing tug of war. Like comic book heroes, women must reckon with bodies that are both battleground and mystery; preternaturally powerful yet somehow never truly their own.

“A lot of the women I draw are based on mythology, on the archetypes that I see across all my female friends,” says Koak, who’s a fan of Dana Schutz and Ella Kruglyanskaya, painters partly responsible for the radical re-imagining of female subjectivity sweeping through the art world and is currently showing as part of On Elizabeth, a group show at Olsen Gruen, New York. “I’m also fascinated with this thing called ‘Parts Therapy’, the notion that every single person has these different archetypes inside them.” She pauses to consider it. “It really fits.”

Over the last few months, Koak has been researching paintings of women bathing, the theme of her upcoming solo show at Alter Space and although the trope, beloved by everyone from Brett Whitely to Cézanne to Degas, seems to me tailor-made for mining the fractured female consciousness — the indignity of being conjured by your lover or surveilled through a keyhole – a few months ago, she started having doubts.

“For women, bathing is one of the most symbolic things you can do, it’s this moment of transformation and reflection and it’s something that people have been painting forever but after Trump won, I was like: ‘women bathing, what is that about?” she laughs. Then again, you only learn to be uncertain when culture teaches you to question your stories. “If you look at some of the older paintings, it’s a bunch of women hanging outside and that’s not how it is for me or any woman I know. They all have the same body type. It’s like, you’re just painting women that you’re attracted to!” She smiles hopefully. “But my favourite sets of bathing paintings are by Mary Cassatt. There’s such a difference in the way she draws women. You notice it straight away.”