First published in VAULT, issue 15.

Lisa Yuskavage isn’t afraid of being too much. The New York artist, who has spent the last quarter of a decade painting a universe peopled by feminine subjects, whose bombshell physicality – legs splayed, breasts swollen – cloak the tawdry thrill of finding an old Penthouse, tucked under your pillow, in the quasi-spiritual glow of a Renaissance fresco, tells me that a queasy response has never put her off.

“Have you ever had someone invite you over for dinner and then start opening cans of food?” she asks me, over the phone from her studio in Brooklyn. “And you’re like, holy shit, you’re inviting me for dinner and all you’re doing is opening up cans of food? What did I come here for? When someone is standing in front of one of my paintings, I don’t want it to be like that. I want them to feel as if I went all out. Maybe they can’t stomach it and prefer canned food but I’d really rather someone have a reaction. It would kill culture if artists made something for everyone. Then you’re really reducing yourself to being ordinary.”

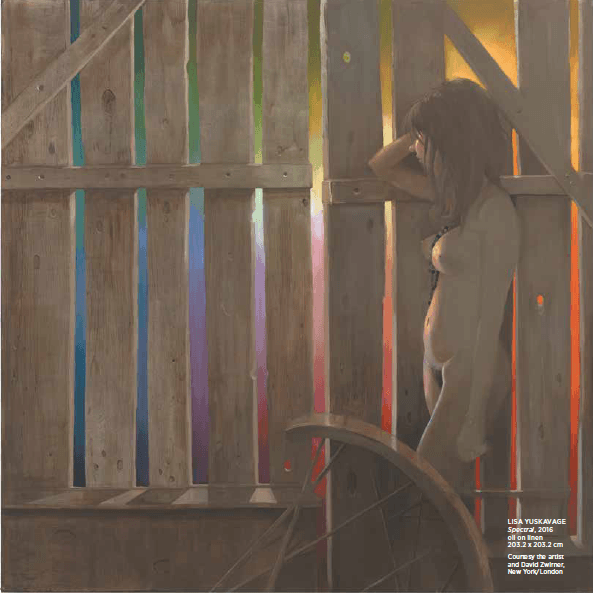

Provocative. Epic. Cynical. Yuskavage has attracted a rollcall of adjectives since becoming famous in the mid-nineties (alongside contemporaries such as John Currin and Elizabeth Peyton) with her Bad Babies series, works in which half-naked women with woebegone expressions press through curtains of peep show red and midnight blue, like deviant escapees from some long-repressed fugue state, but ordinary has never ranked high on that particular list. Whether they’re fondling their lovers, examining their bodies or reclining post-coitus, the characters that populate her paintings are both deeply unsettling and unspeakably beautiful (it’s not for nothing that Yuskavage, who’s been compared to Vermeer, is considered one of the foremost painters of her generation), good girls who wear lace and keep flowers while doing bad girl things. If, like some of her critics, you’re rankled by her work’s smuttier elements, you might believe that morality exists outside respectability, rather than that what we often deem immoral is sometimes just not respectable enough.

“Years ago, an astrologer told me that as a provocateur, I performed an important role in society and someone has to stimulate these kinds of conversations,” laughs Yuskavage, who, a world way from the steely presence I’d been imagining, speaks like your best friend’s older sister, seesawing between fierce intelligence and real-talk candour. “If you’re just stirring the pot for the sake of stirring the pot, you can’t always predict what it’s going to do. But I think that I intend to show a much richer, layered image of an inner life and an inner life has many voices. I like to think the Pope struggles against his bad nature too.”

Yuskavage, who grew up in the sixties in Juniata Park, a working-class Philadelphia neighbourhood, never felt like she had to subscribe to an unspoken code. “Although I’m from a very specific kind of American family, where everyone around me came from parts of Europe, Italy and Lithuania and are first or second-generation European peasants who never had an education, there was always this push that we came here for better things,” says Yuskavage, who is married to the painter Matvey Levenstein, a political refugee from Russia, who she met in the eighties at the Yale School of Art. “My mother came from this very large Irish Catholic family and it was always the women who would be making food, cleaning up and talking but if you mentioned the word ‘feminist’ – and this was very typical for the ‘50s and ‘60s – they thought ‘lesbian.’ But it was clear that my sister and I were going to go to college and for anything we wanted. The questions of feminism were just a matter of commonsense. They never put limits on their girls or questioned what their girls might become.”

At school, Yuskavage, who was part of an advanced placement program, would take excursions to museums and galleries in Philadelphia and, once, found herself sitting in front of a painting by Van Gogh. Although she’d never had an aptitude for drawing, she felt a “near-psychic” connection, a voltage that galvanised her decision to attend Philadelphia’s Tyler Art School and later, apply for an MFA at Yale. Like Yuskavage, I remember how coming across Warhol stills an empty gallery as a teenager woke me up to a world beyond identikit suburbia. Electricity has a way of ricocheting through a life.

“If you expose poor kids to culture, you just don’t know what you’re going to get,” says Yuskavage, who has shown everywhere from the Royal Academy of Arts, London to the Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo in Mexico City and whose works, which have fetched as much as $1.3 million at auction, according to an April 2015 article in The Wall Street Journal, are held in museums including New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art as well as the Art Institute of Chicago, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “But it took a long time to work out what kind of artist I was – did I draw? Did I dance? When I was at Yale, most of my friends had already had private tutors and when I was at art school, my mother said that she’d never seen anyone work so hard in her life. You know when Michelangelo said he’d always seen David in the marble and all he had to do was chip away at it? I really think that life is just a combination of chance and something genetic. I was always meant to be making the work that I make.”

But like most twenty-something artists whose hopes for their work eclipse the life they need to live to make it, Yuskavage struggled to find her voice. In 1990, she showed a series of masterful nudes as part of her first solo exhibition at New York’s Pamela Auchincloss Gallery but the paintings so out of sync with her vision, she barely recognised them. Then 27, she spent a year sitting in an apartment in Ludlow Street, watching movies by the directors Tarkovsky and Fassbinder but it wasn’t until she came across David Lynch’s 1986 classic Blue Velvet that Yuskavage saw the shape of things to come. Her 1991 painting The Gifts, which shows a woman, nipples erect, against a jewel-green background, embodies a mood of horror and desire so startling it seems to sit outside art-historical contexts. Like Diane Arbus, whose portrayal of freakish outsiders holds a mirror up to our best and worst instincts, Yuskavage suggests that the otherness we fear isn’t outside us but lurks within. Unsurprisingly, she is an ardent fan of the late photographer. “Lady was truly a genius,” she recently posted to Instagram.

“When I was offered that first show, Pamela kept insisting that I was a really good painter and I kept feeling that it wasn’t who I am,” recalls Yuskavage, who’s about to travel to China for a group show at the Long Museum in Shanghai. “I don’t make tasty little crumpets. I wanted to make something that is much more complicated and reflective of my nature which is full of love but also full of vinegar and is a much more layered kind of an object. I wanted to talk about vulgar, screaming, punky things alongside beauty and light but assumed that wasn’t permitted. I didn’t recognise the art that I was making. In Blue Velvet, a woman is violated by a character called Frank and he’s sucking some kind of weird gas, being really puerile with her and that was upsetting. But I was like what would it be like to make a painting in the persona of someone I really feared? After The Gifts, I felt like I was breathing actual air because I’d assumed the enemy’s voice and found the voice of complexity, my own voice. It’s this sense of internalising the enemy and understanding that the enemy is in you.”

This voice of complexity is also a portal to that uneasy place in which multiple things can be true. Brood (2006), which showed as part of Lisa Yuskavage: The Brood, a 2015 survey at the Rose Art Museum near Boston, Massachusetts, sees a heavily pregnant woman in front of a fruit bowl, awash in storybook pink. Its sensuous palette winks at a tradition that turns woman into deities, monstrous curves at a culture in which female bodies are still abject, policed and controlled. Hippies (2013), features four impish figures, including the guys that have started to materialise in her pictures, protruding from either side of a colourless nude. It feels like an apparition, like something that wasn’t painted as much as it was divined into being. And when paintings have lives of their own, they can speak to those who exist outside art history. Maybe even those looking for permission to be a little too much themselves.

“After my first show, I realised the very particular voice that I could speak in has never been heard and when I get backlash I realise that it’s impossible to recognise what you’ve never experienced,” she smiles. “Recently, a young African-American kid came to photograph me for a magazine and he said, ‘Can I just say you are one of my biggest influences?’ He had walked into the Whitney Biennale and seen my work and realised that, as a young black man, something about it spoke to him. He said, ‘you’re a badass and I want to be a badass.’ Going into that museum as a kid, seeing the painting that was hanging there, changed my life and that’s why art needs to include the voices of people who they’ve never heard from before whether they’re women or those from other classes. Not just in their own community but beyond that.”

Lisa Yuskavage is represented by David Zwirner, New York.

yuskavage.com

davidzwirner.com