First published on SBS Life, September 2016.

“Power seeks to enclose beauty—to make it scarce, controlled. There is scant beauty in militarised zones or prisons. But beauty keeps breaking out anyway, like the roses on that Ferguson street.” A few weeks before I read those sentences, taken from an August 2014 Vice essay by the New York artist and journalist Molly Crabapple, a teenager called Tamir Rice had been murdered by police in Cleveland and, days earlier, a gunman held workers hostage in a Martin Place café. Crabapple’s words, written in the aftermath of Ferguson, reminded me that beauty can anchor us when the world spins off its axis. I didn’t realise that I needed to hear them until my eyes welled up.

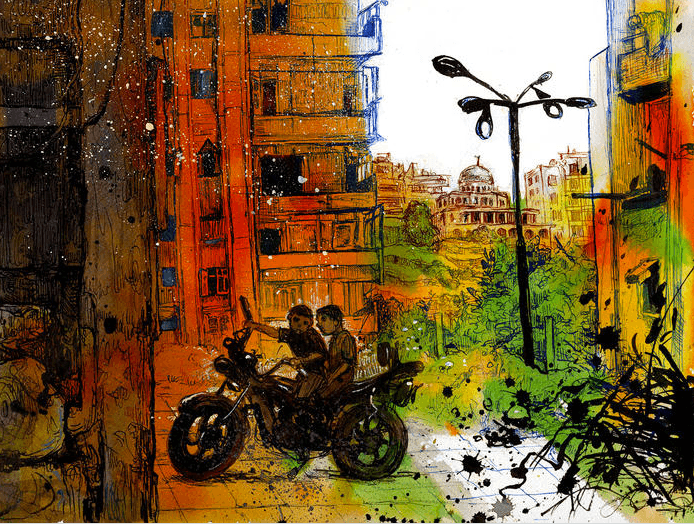

Over the last decade, Crabapple has used art and, later, journalism to chronicle the moments that have defined the early 21st century but her work prompts a visceral reaction because of its willingness to stare down power before committing it to ink. Although Crabapple honed her style — a mishmash of punk-show energy and gimlet detail — at The Box, a Manhattan Burlesque club that doubled as a holding pen for high-rolling bankers, she made her name with her visual account of Occupy Wall Street and illustrated dispatches of Guantanamo Bay, migrant labour camps and life under ISIS for places like Vice and Vanity Fair.

“I’ve been drawing since I was a little kid,” grins the flesh-and-blood Crabapple, who I’m speaking to in a weirdly utilitarian chamber of the Opera House, where she’s presented as part of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. “My mother is an artist, my grandfather is an artist. I was just always obsessed with it – at first my obsession far outstripped my ability. I used to be one of those brats who would be pounding my fists saying that what I was drawing was ugly, his hands look like claws! But drawing had stuck its claws into me.”

Crabapple’s memoir, Drawing Blood, follows her trajectory from suburban misfit (she was born in Queens) to Shakespeare and Company, the Paris bookshop known for housing vagabond writers to the hardscrabble toil of making a living in a New York where trust funds and Trump towers had all but vanquished the ghosts of artists past. For Crabapple, who supported herself as a nude model, a turning point came when Occupy Wall Street unfolded minutes from her apartment. Her surrealist paintings of the global financial meltdown lent the revolution a visual language. Two years later, Vice sent her to Camp X-Ray, a brutal Guantanamo Bay prison camp (“everyone lives in outdoor cages, with no shade, only buckets. When you’re there your skin crawls”). She also travelled to Abu Dhabi, where she worked with a fixer to expose the plight of migrant workers who are forced to surrender their passports and can earn just $150 a month.

In December 2015, Crabapple, who’s also confronted Donald Trump about his labour abuses and documented the hearing of 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, visited Domiz, a camp in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is home to 40,000 Kurdish Syrian refugees. Crabapple, whose portraits of refugee families possess an empathy that’s absent from a global conversation that reduces human life to a geopolitical chess game, says that we’re being sold convenient fictions about the power of borders and the circumstances under which people leave behind everything they know.

“The first moron fiction about refugees is that they’re all impoverished, starving people — the reason that they’re going on boats and not planes isn’t about charity it’s about oppression,” she says. “The refugees in Iraq may have escaped the physical danger of bombing but there were also in a place where there was no work and their kids couldn’t go to university. That they were making the trip to Europe because it was an unstable hopeless life with no future. Otherwise, they would run through their savings, live in a tent and get nothing. There is no hard line between refugee and migrant. Rich people who are born in rich countries have passports that allow them to move and people who are born in poor countries don’t.”

I ask Crabapple, who’s working with collaborator Marwan Hisham to co-write and illustrate a book about the Syrian War, why we should cling to beauty when things seem so dark. “If we don’t have anything that we’re for, we don’t have any good arguments about the world we want to build,” she smiles. “Art can show us what kind of world we want to live in.”