First published in VAULT, issue 17

The Star Hotel, a spangled extension of Sydney’s flashiest casino is usually no place for anything but a deep sense of nihilism unless, of course, you happen to be in the company of the American artist Nick Cave. In his presence, gilt-plated surfaces and marble walls and even the distant brring! of poker machines seem less bleak than they could be. This is probably less grounded in reality than it is in Cave’s singular talent for alchemy. After all, the artist’s installations, performances and Soundsuits — wildly theatrical sculptures designed to be shrugged on and off — have alerted the world to the extraordinary dimensions of ordinary settings and transformed the darkest matter into the stuff of magic for the past two decades.

“Honey, we must keep dreaming,” drawls Cave, who’s in Sydney for the Australian premiere of HEARD, a performance that premiered at New York’s Grand Central Station and sees dancers morph into swashbuckling horses, the colour of Play-Doh, before shimmying — like the acid-bright heirs to Josephine Baker — back into dancers again. “Dreaming is optimism. Dreaming is how we know what the future is going to look like. It elevates us and motivates us. It keeps us working towards something higher and bigger.”

Cave, who grew up in Fulton, Missouri, with six brothers and a single mother has always known that even the most humble creative gestures can transport us to fantasy realms. “As a kid, my mother put a sock over her hand — instantly, it became a puppet and I was right there with her!” laughs Cave, sprightly in a white tee and cargo shorts, the faintest trace of a salt-and-pepper goatee the only nod to his 57 years. “I have an older brother Jack, who’s also an artist and we would set up still lifes in our house. It was always about who could draw it faster than the other, who could paint it the quickest.”

He went on to study art at the Kansas City Art Institute, training for a semester with a member of the legendary Alvin Ailey dance troupe and started teaching in the fashion department of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1990, after earning his Master’s from the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Although Cave took part in weekly studio critiques with a circle of friends, he remained fiercely pragmatic. “I’ve never believed in the idea of the starving artist,” he muses. “My mother was like, ‘get a job, you’ve got to take care of yourself — I’ve got six other boys to raise.’ Art school was great and I loved being in that world. But I have thousands of friends who are artists, who are established at different levels of their practice. Not everybody gets a break.”

The year after Rodney King, an African-American taxi driver was beaten by four white Los Angeles police officers — a crime that sparked the LA riots and permanently altered the discourse on race in America — Cave found himself on a bench in Chicago’s Grant Park. He spotted some twigs on the ground, wove them into a sculpture and decided, on a whim, to weld his creation to a garment. When he put it on, the branches rustled loudly. Without meaning to, he’d made his first Soundsuit. Something inside him, he tells me, had changed for good.

“The 1991 Rodney King beating was so disturbing to me as a young, black man,” says Cave, who recently created TM 13, a soundsuit to commemorate the killing of young African-American man Trayvon Martin and who mentored students from the Detroit School of Arts as part of Here Hear, a 2015 series of public performances that aimed to galvanise a city that’s long been divided along racial lines. “I picked up those twigs because I saw them as material that was discarded, dismissed — and that’s how I was feeling. When I wore them, they made a sound and it made me think about the role of protest and that if you want to be heard, you have to speak out loud. I’d been victimised before and it made me discover what really mattered. At that moment, I knew I wanted to be an artist that worked with a sense of civic responsibility.”

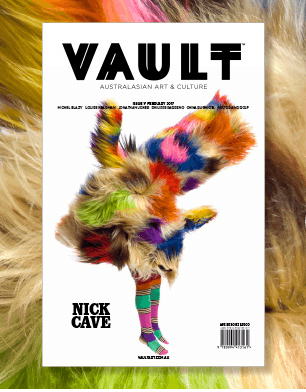

Glittering sequins. Ceramic flowers. Human hair in rainbow colours. Buttons. Cave’s Soundsuits, made out of scavenged material in his Chicago studio, are so dazzling and hyperbolic in both aesthetics and construction, it’s easy to forget that they’re supposed to serve as armour for those who — by virtue of race, class or gender — are rendered invisible, restricted from moving freely through the world. The suits, which are held by MoMA and the Brooklyn Museum and can sell for up to $150,000, according to a May 2016 report by Sotheby’s, (if you like, can buy your own online) also turned Cave into an unlikely celebrity. He’s “like a rock star in the art world,” his New York dealer, Jack Shainman told ArtNews in May 2016. “The attention was overwhelming,” confesses Cave, who spent the nineties co-running Robave, a Chicago fashion and furniture label. “I wasn’t mentally ready to take on the responsibility, so I went underground for ten years. I worked across different mediums. But I had a calling that brought me back to this work.”

Over the last few years, Cave’s “work” has taken the form of sprawling spectacles that tap into the life force of different places, blur the lines between art, fashion, performance, dance and music and take audiences, who might be marching, robot-like, through daily existence, to a higher state. Until, an immersive installation that opened in a hangar-sized space at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MassMoCA) last September and runs until October, intertwines 24 shimmering chandeliers, nearly 17 kilometers of crystal and millions of plastic beads with guns and dark-faced lawn jockeys, American garden statues that are now widely considered offensive. The project, which was co-commissioned by MassMoCA, Carriageworks and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and will host panels and new works by choreographer Bill T. Jones, soprano singer Brenda Wimberly and Sereca Henderson, a singer who worked with B.B. King, is both performance space and installation. “The year MassMoCA offered me the show, there was so much outrage around Trayvon Martin, Freddie Gray and Sandra Bland and I was interested in creating a safe haven where artists and performers could have these conversation with community leaders. But I have to be sensitive about how I incorporate these issues within my practice. If it’s too direct, it doesn’t work,” he sighs.

The morning before I meet Cave, I watch a herd of raffia horses clomp in circles around the concrete floor of Carriageworks while a group of Samoan drummers provide a heavy, dirge-like beat. As the drumming intensifies, the horse transform into dancers, sashaying left and right with such joy and efficacy, the hush that swept through the audience moments before dissolves into a delighted, incredulous laugh. Later that day, I quiz Cave, who choreographed the performance with long-time collaborator Bob Faust and 30 local dancers, what he’s planning in the future and whether he’s cowed by the scale and sheer interdisciplinary ambition of his work. “Whether you’re painting, or sculpting or performing, everything comes down to presentation and display,” he tells me. “We have a big election in a day and I just want to stay relevant and find new ways to work with the community. I’m a messenger before I’m an artist, I just say what I need to say before I move onto my next assignment.” As I shake Cave’s hand and walk into the grey evening, I can’t help think about how much the world needs to hear his messages right now.