First published on VICE Weekends, November 2016.

Victor Gruen was a serial optimist. Back in 1952, the Austrian architect who dreamt of bringing the cosmopolitan atmosphere of his native Vienna to the identikit streets of Middle America built the world’s first enclosed mall in Edina, Minnesota. The Southdale Centre was a split-level oasis where white, middle class shoppers could stroll through indoor boulevards and convene around indoor ponds, fringed with foliage. Best of all, they could buy whatever they wanted in air-conditioned comfort, protected from the unsavoury parts of the population that might greet them downtown.

This indoor utopia became the model for more than 1000 shopping centres that multiplied across the US in the next four decades—along with Brisbane’s Chermside and Melbourne’s Chadstone, both built in the late ’50s as part of Australia’s own mall craze. Gruen eventually became disgusted that his community hubs had morphed into sky-lit wastelands, thanks to post-war tax laws that made big developments seriously profitable.

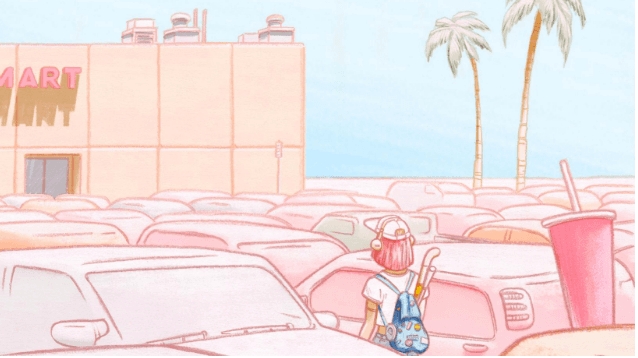

He never could have guessed that for the generation of teenagers who grew up in ’90s suburbia, life would play out in malls called the Forum, the Palms, or the Plaza—names that were designed to evoke the town squares of Ancient Europe, but instead managed to intensify the reality of suburban existence. When you’re hours away from anything resembling an urban experience and years away from the around-the-clock thrills of the internet, there was nowhere else you could go.

It’s easy to dismiss ’90s malls as soulless shrines to consumption, home to crappy food courts, and embarrassing mid-market chain stores. But doing so ignores the ways in which these places gave teenagers a sense of connection with each other, as well as the freedom to be themselves. As a teenager, Saturdays and school holidays were spent with my friends, drifting up and down the escalators or circling the faux-Milanese atrium, the focal point of an exceedingly average Perth mall called the Galleria. We’d stop to try on Doc Martens that were out of our price range or cowl neck minidresses meant for nightclubs we were too young to go to. These unsupervised hours were our first real taste of adult freedom. The inward-facing nature of mall architecture let us indulge in our friendships and be as insular as we wanted to be—we were free to simply drift, to take up space. The things we did buy, like strawberry lip balms from The Body Shop and albums salvaged from the discount rack at Sanity, didn’t feel like consumer items, they felt like the evidence of our bonds.

And yeah, ’90s malls were home to shops like Foot Locker, Surf Dive N’ Ski and Myer (if you were lucky), but the blandness of that era’s brand worship was weirdly accommodating to difference as well. If you were into hip-hop or surfing or metal, you could, in that teenage way, find your sense of self in a pair of high-tops and display your allegiance to your subculture. If you were a nonwhite kid, those sliding glass doors were a portal to a life you didn’t often have access to and became the only time you go to be a regular Australian teenager. You could find your people at the mall whether you were Dionne from Clueless or Brodie from Mallrats. Even if consumerism was partly responsible, there was something special about that suburban sea of sameness that felt profound.

In the last decade, our tastes—thanks in part to the internet—have changed. You’ll find artisanal donut shops and Michelin-starred dumpling houses in place of anonymous carveries. Laminate food courts now have Scandinavian furniture and copper fixtures, and boutiques offer pop-up yoga classes or events promising “cocktails and conversation,” which are the antithesis of aimless roaming.

An April 2014 study by Piper Jaffrey found that teen mall traffic has declined 30% over the last decade. In January 2015, the ABC reported that half of America’s shopping malls will disappear in the next 15 years, with a similar fate predicted for Australia. According to a more recent article in The Sydney Morning Herald, shopping centres like Chadstone, Knox, and Doncaster are facing billion-dollar renovations in order to keep up with the current preference for online shopping.

When you browse the abandoned atriums and taped-up escalators of Dead Malls, it’s easy to pretend that the mall was never relevant, but it’s at least proof that the things we valued then are simply different from the things we value now. It’s not that artisanal is inherently better than generic or mainstream—the way we consume has skated towards the curated and experiential. The teenagers in the Piper Jaffrey survey don’t go to the mall to buy clothes or ride escalators; they prefer to spend their time in fancy restaurants.

As wealth has poured back into the cities, sprawling suburban shopping centres no longer symbolise affluence, but signs of decay. We need stories to exonerate ourselves from the conformity that the suburbs supposedly represent. Renouncing your mallrat past is one way to do that—even if those teenage summers spent cruising the mall with your friends were some of the most formative times of your life.