The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane eschews the Western art world’s reliance on checkbox diversity in favour of genuine immersion in our region.

First published in The Saturday Paper December 1, 2018.

In the weeks before the opening of the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) at QAG and GOMA in Brisbane, a New Yorker article by Margaret Talbot materialised again and again on my Twitter feed. ‘The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture’ explores our ignorance of polychromy, the practice of painting artefacts in different colours. This ignorance erased non-Europeans from defining aesthetic traditions. It also — quite literally! — helped cast whiteness as both signifier of beauty and arbiter of value. Sure, today’s rollcall of biennales and triennials, often helmed by globetrotting celebrity curators, challenge our populist, post-Trump era. But they often do little to upend these endemic power structures. Too often, artists who’ve been producing exemplary work, sometimes for decades, beyond the limited reach of the Western art world are given a platform in service of a checklist diversity, invited to perform their identity. Or worse, their trauma. To borrow a term from the African-American philosopher George Yancy, the white gaze remains intact.

APT, an event whose 25-year old history predates this current fixation with performative wokeness, is the largest exhibition devoted exclusively to contemporary art from the Asia Pacific. (And, remarkably, the only one to position Australia within this context.) The show was overseen by Dr Zara Stanhope and an in-house team who’ve deeply immersed themselves in the region’s countries and art scenes — an imperative that does a lot more for the presentation’s depth and vitality than the nebulous “themes” so beloved by curators. It features upwards of 80 artists and collectives from 30 countries including — for the first time — Bangladesh, Laos, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Solomon Islands and the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, a constellation of atolls that was once part of Papua New Guinea.

The 400-strong series of artworks represent a universe of artistic styles and practices: monochrome photographs and rainbow-bright assemblages, woven basketry and high-concept video art. Threads recur. Some pieces deal with tangled colonial histories and the attendant feelings of displacement and longing. Others with nature, flux and matriarchy. But navigating the bottom floor of QAG and GOMA’s airy, sun-splashed galleries, the idea that sprung to mind isn’t diversity (diverse to whom?) but plurality. The notion that there is no one way to make art or, indeed, see art shouldn’t strike me as fresh, exhilarating or downright radical. I’ve become so accustomed to the invisible presence of the white gaze, especially in rarefied spaces like galleries, that it does.

Over the last two years, the art world has been understandably preoccupied with politics. In some ways, grappling with the tyranny of borders, the scourge of racism and the fallout from the refugee crisis has never felt more necessary. The trouble is that so much work that brands itself as political — take Ai Weiwei’s Law of the Journey at this year’s Biennale of Sydney — comes off as empty and bombastic, designed to mirror rather than expand our worldview. As Stanhope, referencing the Indian art historian Geeta Kapur, points out at the media preview, APT is as concerned with poetics as it is with politics. The show pays attention to how the forces of history don’t just shape global events but can refract, fragment and transform the consciousness of its subjects. This gives rise to some of its most poignant moments.

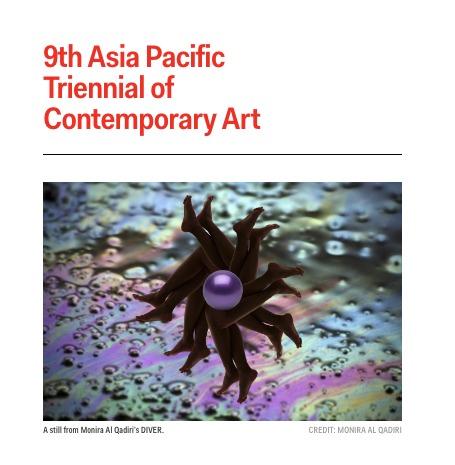

In a darkened gallery at GOMA, I sat mesmerised in front of Monira Al Qadiri’s DIVER (2018). The four-channel video work, which sees synchronised swimmers duck, dive and spin to haunting Kuwaiti pearling songs, is a study in viscous, prismatic surfaces. It sparks aesthetic parallels between the Persian Gulf’s 19th century history of pearling — the artist’s grandfather was a singer on a pearling ship — and the modern-day oil boom, an industry equally implicated in human and environmental exploitation. The work conjures both the languid pleasure of gliding underwater and a push-pull between desire and terror, the sensation of drifting towards something whose contours are both familiar and unknown.

Elsewhere, the aftermath of historical narratives sparks new ways of recouping cultural practices and reclaiming collective memory — to powerful effect. Nearby, Ly Hoàng Ly Ashes (2013), the result of the Vietnamese artist’s attempt to simmer cow bones for her daughter while living in Chicago, tenderly evokes the way homeland rituals become phantom limbs in the lives of immigrants, doomed to be replaced but never recreated. Over at QAG’s Watermall, the Singaporean artists Donna Ong and Robert Zhao Renhui riff on the ways in which the city-state’s lush tropical jungles are filtered through the colonial imagination in My forest is not your garden (2015-18). The installation channels the botanical displays that adorn the lobbies of luxury hotels in big Asian cities, exoticism internalised and spat out for Western consumption. To me, it also nods at the troubling yen for Empire-era interiors across bars in places like Melbourne and Sydney.

Back at GOMA, the Alice Springs portraitist Vincent Namatjira, the great grandson of the legendary Arrernte landscape painter Albert Namatjira and part of the Triennial’s largest-ever cohort of First Nations artists, playfully skewers the hypocrisy that underpins the distribution of privilege in Australia. Three 2016 series, Seven Leaders, Prime Ministers and The Richest, pit the artists and law-men who helm South Australia’s APY communities with Australia’s richest magnates and the country’s last seven leaders. The latter represent an in-joke that references their wilful disregard for Indigenous sovereignty. It also winks at the self-interest that’s seen each leader’s hapless grin become interchangeable over the last few years.

The Triennial has always commissioned monumental pieces, sometimes in partnership with major Asian institutions. This year’s highlights include For, In Your Tongue, I Can Not Fit (2017-18), a room affixed with microphones that relay fragments of verse from Indian new media pioneer Shilpa Gupta and an audacious, Technicolour mural by Iman Raad, an Iranian artist whose practice references Mughal painting and the intricate artwork that adorns buses in South Asia. Along with freewheeling mixed-media paintings by Filipino artist Kawayan De Guia and giant rings of cane or Loloi, created for APT by the Tolai people of New Guinea, Raad’s work reflects the exhibition’s commitment to elevating vernacular art forms alongside the pieces we might see in a gallery. This feels subversive for a Western institution. It’s also a reminder that those of us who grew up outside this context have long suspected that the aesthetics of everyday life may have as much to say as paintings and sculptures when it comes to how we see the world.

APT has a kaleidoscopic sensibility. So much work here is wildly ambitious, aimed at widening our visual horizons and elevating undersung artists. But not everything is executed to equal effect. Chinese artist Qiu Zhijie’s Map of Technological Ethics (2018), an epic painting that adorns the main wall of GOMA’s Long Gallery, draws on calligraphic traditions to map the moral landmines — artificial intelligence, climate change — that define our cultural moment. The brushwork is gorgeous, but the notion of imagined geographies doesn’t feel distinct enough to live up to the work’s aspirations. I tended, instead, to connect most with quieter explorations of the natural world. An example: the exquisite Untitled (giran) (2018) an installation in which 2000 winged sculptures, made from tools such as emu eggshell spoons, animal bones and feathers mine the connections between the breath and wind, language and Country by Kamilaroi/Wiradjuri artist Jonathan Jones.

Similarly, Women’s Wealth, a first-time project that foregrounds the cultural practices — weaving, pottery and adornment — at the heart of matrilineal communities in Bougainville is admirable in its intentions. I think it could have delved a little more into the way in which the erasure of female labour continues to uphold capitalist systems and underpin the way entire societies are run. But the fact that this edition of APT plays host to more women than male artists also allows for a range of intriguing and specific perspectives on female agency. Taiwanese artist Joyce Ho’s video work Overexposed memory (2015), which sees a manicured hand plunge its fingers, ever-so-slowly, into pulpy, hyperreal fruit, revelling in the juices that spurt out nods at the porous nature of the female body. It hints at the way being a woman often means being caught between the sensual and the abject, the ordinary and the sublime. Dark Continent (2018), an image by Latai Taumoepeau features the Tongan performance artist covering herself with spray-tan. The work, which symbolises white Australia’s fetish for tanned skin, reveals the relationship between colour, power and value. It also tries to reframe it. In the end, this may be the best metaphor for APT’s project itself.

The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial shows at QAG and GOMA shows from 24 November 2018 to 28 April 2019.