First published in SPECTRUM in the Sydney Morning Herald, March 2021.

In Lin-Manuel Miranda’s world, writing is never just a form of self-expression. Words, strung together, can remake entire realities. Wield them a certain way and you have a revolutionary force.

The playwright, actor and composer won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Hamilton, the virtuosic musical that re-imagines the life of Alexander Hamilton, an orphan from the British West Indies who designed America’s central banking system. But he grew up the son of Puerto Rican immigrants in New York City’s Inwood, where over a third of the community is overseas-born, to a soundtrack of show tunes and hip-hop.

Miranda took Alexander Hamilton, an 818-page biography by Ron Chernow on a 2008 holiday with his wife to Mexico. Forty pages in, lightning struck.

“I felt like I had read a whole Dickens novel, just the sheer tragedy of this kid’s young life,” Miranda, who’s wearing a grey sweater and newsboy cap and radiates the incandescent energy of his own characters, tells me over Zoom. “I had a few thoughts. First, this reminds me of my father who also wrote his way out of the Caribbean. Two, it reminded me of my favourite hip-hop artists. I can write under a pseudonym and that is my ticket out of here.” He dissolves into laughter. “That’s Reasonable Doubt. That’s Ready to Die. Pick one.”

Hamilton wrote his way out via a newspaper account of a 1772 hurricane. It was so eloquent his fellow citizens sent him to study in New York City. There, he became a Founding Father and co-wrote The Federalist Papers, a series of essays that ratified the Constitution.

Miranda’s own father, Luis A. Miranda Jr., moved to the states as a teenager, studied at New York University and became a political consultant. Ready to Die’s author, the late, great rapper Christopher Wallace – aka The Notorious B.I.G – was also the son of Jamaican immigrants.

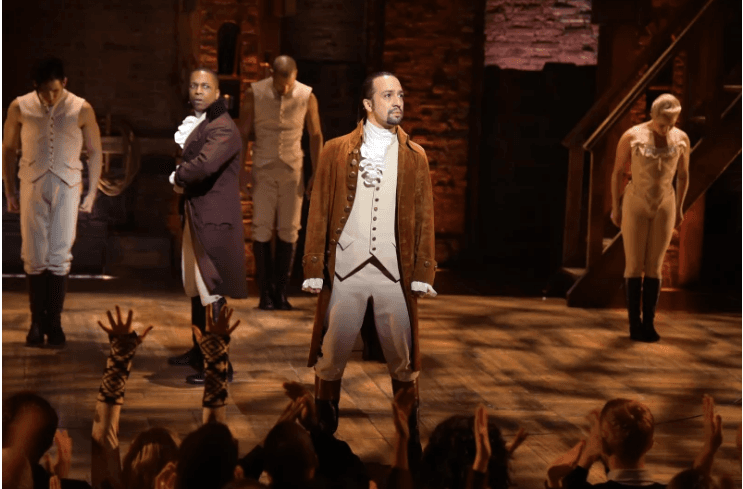

Miranda played Hamilton in the original 2015 production, which premiered at New York’s Public Theatre. In Act One, he bursts into My Shot. The problem is I got a lot of brains but no polish/I gotta holler just to be heard/With every word, I drop knowledge, he raps, pacing the stage in a waist-coast and breeches.

My Shot samples Wallace’s 1997 hit Back to Cali. It declares Hamilton’s smarts and ambition. It also compresses the complexity of the immigrant experience into five-and-a-half electrifying minutes. Its intricate rhymes speak to resourcefulness and sacrifice, the sense of life as a series of high-stakes opportunities, the hunger to be seen.

This month, Hamilton opens in Australia where according to 2019 figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 30 percent of the population was born in another country. Hamilton’s Australian production features 33 Australian performers who span West African, Latino, Mauritian, East Asian and First Nations backgrounds.

Hamilton, produced in Australia by the Michael Cassel Group, coincides with a watershed moment in the conversation about cultural diversity in Australian theatre. Last year, graduates of the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) wrote a letter that addressed systemic racism at the institution. The Rob Guest Endowment, a scholarship for musical theatre talent was criticised for naming an all-white group of semi-finalists. In response, groups such as We the Industry and The Quarter have been campaigning for equality across the sector.

How to describe Hamilton’s magnitude? Along with eleven Tony Awards and high praise from Michelle Obama, the show has been lauded for its commitment to colour-conscious casting, prescient in the age of Trumpian border walls and Black Lives Matter.

Miranda compares assembling the Australian cast to running a four-minute mile. “As soon as someone broke it, everyone started breaking it,” he smiles.

He’s more circumspect about hiring actors of colour to play white historical figures.

“I was writing in an art form that was created by Black and brown artists in the Bronx in the 1970s,” he says simply. “If Hamilton had an all-white cast, wouldn’t you think I’d f—-ed up?”

*

Jason Arrow has been expressing himself for as long as he can remember. The actor and singer-songwriter whose family immigrated to Perth from Durban self-identifies as ‘coloured’, the South African government’s official term for communities of mixed heritage.

Growing up, Arrow listened to his parents’ Earth Wind and Fire records and the ‘90s R&B beloved by his sister. He put on New Year’s Eve performances. He honed his skills in Perth’s amateur theatre scene. He studied electrotechnology. Then he threw it in, to pursue acting, performing in stage shows like Disney’s Aladdin and Beautiful: The Carole King Musical.

In some ways Arrow, a statuesque presence who speaks with an unshowy sensitivity has been preparing for the role of Alexander Hamilton – a relentless improvisor who sacrificed certainty for destiny – all his life.

Hamilton’s mother died when he was 11. Arrow believes that the tragic circumstances responsible for his character’s inner fire also give rise to his poor decisions – such as an affair that he detailed in a document called the Reynold’s Pamphlet.

“It took me a little while to like the guy, but I realised why he was the way he was,” he laughs. “He didn’t have a family so of course he doesn’t know how to handle relationships. He had to create his legacy. It wasn’t handed down to him.”

For Arrow, becoming Hamilton means tapping into his own personal story. “I admire Hamilton’s ability to move forward,” he muses. “My parents had to do it. We had nothing. But they moved and made a life for themselves.”

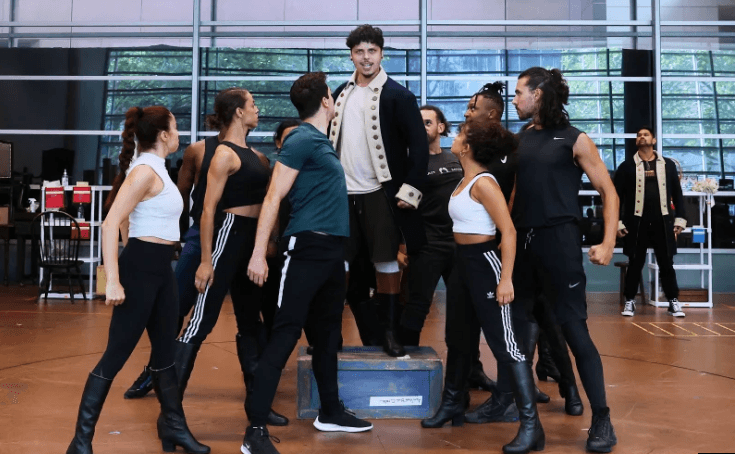

Once Arrow auditioned, Miranda knew he’d found his Hamilton.

“The last verse of My Shot [is] one of the hardest to get your breath control around,” he says. “You want folks that are not winded but energised by it. I remember that very clearly from Jason’s audition. He ate it. He ate it like he was starving.”

*

Like Arrow, Chloé Zuel has been performing since childhood. The early years of her life played out in suburban Sydney where her grandparents and single mother shuttled her to dance classes and eisteddfods. By any account, the Mauritian-Australian performer, who’s warm and gregarious with a megawatt smile, has had a dream trajectory. She received rave reviews as Anita in 2019’s West Side Story. She sang at last year’s NRL Grand Final. But she’s also suffered bouts of anxiety.

“I didn’t have the vocabulary to express how I felt about being a person of colour within the industry until recently,” she says. “You need to tell yourself that you are enough. I didn’t realise how much I was searching for validation. Singing itself is such a vulnerable way of being.”

A few years ago, Zuel put Hamilton on her vision board. When we talk, she’s deep in rehearsals for the part of Hamilton’s wife Eliza Schuyler, a spirited socialite who helps her husband draft essays. In ballads such as It’s Quiet Uptown, she conveys her grief at her husband’s betrayals – and the strength it takes to release them – with an exquisite intensity.

“I think Eliza is the hero of the story,” Zuel says. “Lin has given us a show that insists upon diversity. Then he gives us these characters that are so relatable. It’s a gift of a role.”

The shop owner. The criminal. The feisty sidekick. In the last few years, Australian playwrights have been addressing the cultural whiteness that has shaped theatre but it’s easy to forget the insidious history of racial tokenism. Or that up until the early 1970s, Australia still staged minstrel shows.

Akina Edmonds plays Angelica Schuyler, a fiery intellect who finds her match in Hamilton but puts her feelings aside out of respect to Eliza, her sister. On meeting Edmonds, an Aotearoa-born performer of Maori and Japanese descent, I’m struck by her actorly charisma. She pulls faces with her co-stars. She juts her chin and instantly I see Angelica’s intelligence and dignity.

For Edmonds, who starred in Sister Act: The Musical and appeared on The Voice in 2019, Hamilton isn’t just about centring actors of colour. It’s about exploring a depth and breadth of humanity on stage.

“I’m discovering that in the rehearsal room, I play a complete woman, not just the token friend who’s giving it sass in the corner,” Edmonds smiles. “It’s that balance between strength and vulnerability, a thick skin and soft heart. That is something very exciting.”

The impact of Hamilton goes beyond the value of representation. By casting actors of colour in a story about the colonists that freed America from British rule, it shows us how bodies that have been excised from history are central to the national story. This is painfully relevant in a country that’s yet to recognise Indigenous sovereignty, that frames immigrants as new arrivals, erasing the ways in which they’ve long shaped society. Not that this is problem-free.

Victory Ndukwe was born in Nigeria, has lived in South Africa and Mozambique and spent his teenage years in Wodonga, near the New South Wales border. The actor and musician, who studied at Melbourne’s 16th Street Actors Studio, plays the Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson, who fought for equality while he was a slave-owner. Ndukwe says that grappling with Jefferson’s contradictions is an artistic challenge.

“The thing I really enjoy is embodying a character and truthfully telling a story,” he says. “If you are trying to play somebody and judge them, it’s not going to work.”

Ndukwe started rapping when he was seventeen. “I never would have believed that I would be doing it in a musical,” he grins. Miranda’s musical heroes, the hip-hop artists of the eighties and nineties, used verse and rhyme and wordplay as a form of protest. They gave old stories a new language.

“Other musicals reference songs that I had no idea about,” laughs Elandrah Eramiha, an actor and RnB singer of Pasifika heritage who plays Peggy Schuyler and Maria Reynolds.

When Shaka Cook, an acclaimed actor and Yinhawangka and Yindjibarndi man who will play James Madison and Hercules Mulligan, was a boy in the Pilbara, Grease was the only musical he had heard of. Cook, who’s starred in productions such as Black Diggers and The Secret River believes that Hamilton owes its power to the history of its form.

“The rap, the hip-hop thing, is powerful– artists like Tupac, Biggie Smalls, NWA came from these harsh environments [but] they wrote their way out,” he says. “I’m an Indigenous person who has grown up knowing Australia’s true history. We are experiencing systems that are still ongoing. Hamilton is giving us a platform to be seen in the world.”