First published in SPECTRUM in The Sydney Morning Herald, June 2021.

Some paintings are worthy of pilgrimage. But for Halina Dyrschka, there are some paintings that are so extraordinary, they are journeys in themselves. In 2013, the Berlin-based filmmaker saw a series of works called The Ten Largest, by a Swedish mystic called Hilma af Klint in a German newspaper. The images transported her so vividly, she lost the ability to describe them.

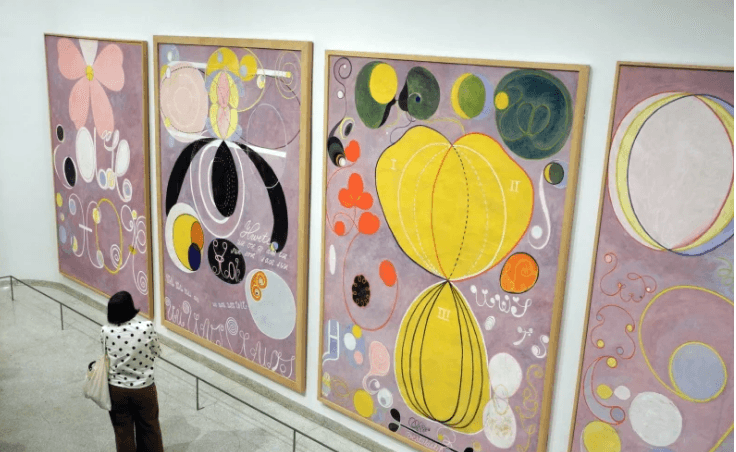

“When I saw her paintings, I thought ‘it cannot be’,” says Dyrschka, who would later visit the exhibition Hilma af Klint: A Pioneer of Abstraction at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. “Standing in front of The Ten Largest, I was speechless. And then I was angry. I thought ‘it can’t be that I’ve never heard of her before.’ Even if you don’t like the paintings, you can’t forget them.” She flashes a wistful smile over Facetime. “They are something beyond art, I would say.”

Dyrschka’s acclaimed 2019 documentary Beyond the Visible re-imagines af Klint in her studio on Hamngatan, near the centre of Stockholm. She bends over a sheet of paper, placed flat on the ground, stretched over a three-metre-high canvas. She dips her brush into a pail of egg tempera, a mix of yolk and powdered pigment. Her wrist arcs. A sun-yellow form emerges. Then swathes of lilac, a dusk-pink snail shell. Orange tendrils bud circles and teardrops. The painting, No 7, Adulthood, made in 1907, appears as if by osmosis.

“The Ten Largest has a very sexual energy – everything is mating, oscillating, flipping, guiding, floating,” says Julia Voss, a German art critic whose af Klint biography will be released in English next year.

No 7, Adulthood, a centerpiece of The Ten Largest, was painted in four days. It was part of a commission from Amaliel, a spirit guide who, in 1904, instructed af Klint to create The Paintings for the Temple. The succession of 193 works, conjured via the astral realm, were intended to fill a spiral building, whose designs suspiciously resemble the Guggenheim, where a 2018 show of af Klint’s work attracted the most visitors in the gallery’s history.

The Ten Largest traces the phases of earthly existence, childhood and youth, old age and adulthood. But the series, on show as part of Art Gallery of New South Wales’ Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings, the artist’s first Asia-Pacific retrospective, achieve something greater. They evoke the human spirit untethered from worldly trappings. They point to cosmic truths that sit outside time and history: swirling, polymorphic and profound.

Sue Cramer has been dreaming about bringing af Klint’s work to Australia since her time as curator at the Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne. “I’ve always been interested in early 20th century abstraction and was amazed by her work, astounded by it,” she says.

Cramer, curated Hilma af Klint: The Secret Paintings in collaboration with AGNSW’s senior curator of international and contemporary art, Nicholas Chambers. Along with The Paintings for the Temple, the show features over 100 works including notebooks, botanical paintings and watercolours, some of which have never been publicly exhibited. She says that af Klint’s work isn’t shaped by the ego that drives her male contemporaries.

Abstract art, at least in the West, has long been synonymous with the likes of Wassily Kandinsky, the intellectually restless Russian émigré who claimed to have invented abstraction with Composition V, shown at a 1911 exhibition in Munich. Kazimir Malevich, whose 1915 Black Square still perplexes artists. Or Jackson Pollock in his Long Island barn in the 1940s, frantically making action paintings.

Af Klint started painting Primordial Chaos, a group of small, blue-and-green canvases that wrestle with the origins of the world through a sequence of radial lines and cryptic symbols in 1906. As Voss points out, she arrived at abstraction first.

“Abstraction only became a success story during the Cold War,” says Voss. “There was the [idea] that it was the expression of individual freedom, that it was created by men – Kandinsky, Pollock. But women were very important.”

History loves to imagine the artist as a lone male genius. But af Klint, who started making her work in the presence of other women, conceived of her art as a conversation with higher powers.

“She’s not making manifestos about the history of art,” says Cramer. “Malevich and Mondrian had a very strict program of progression in their work. Hilma’s is very open-minded. It’s a wide cosmic view of humanity’s place in the universe.” She pauses. “It’s coming from a very different viewpoint. It wasn’t reductive; it was expansive.”

*

Hilma af Klint was born in Stockholm in 1862, part of a respected family of cartographers and naval officers. The death of her 10-year-old sister, Hermina, when she was 18 sparked a fascination with Spiritualism, a movement that believed in a dialogue between the dead and the living. “It’s an interest she had in common with numerous artists and intellectuals all through Europe,” says Chambers.

Interestingly, Spiritualism, popularised by Russian philosopher Madame Helena Blatvasky, who co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875, welcomed women, thought to be better suited to the work of mediumship.

“The ‘founding fathers’ of abstraction were interested in different spiritualist belief systems,” he adds. “But there were spiritualist movements of this time run by women. Hilma’s work paints a richer and complex picture of the story of modern art.”

In 1882, af Klint attended Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, where she was a top student. Later, she earned a living as a painter and illustrator, making intricate studies of plants and flowers on paper. Then, in 1896, she starts holding seances with The Five, four friends from art school, including Anna Cassel, with whom she forged a lifelong connection.

The Five filled notebooks with automatic writing. They communed with the spirit guides or High Masters, Gregor, Clemens, Amaliel and Ananda, making joint pastel-and-graphite drawings of petals and spirals, droplets and eggs. Organic forms, both otherworldly and familiar.

In Europe at the turn of the 20th century, says Jessica Höglund, CEO of the Hilma af Klint Foundation, science and Spiritualism were entwined with each other. Thomas Edison built a machine to speak to the dead. Marie and Pierre Curie had links to the occult.

“So many things happened in the beginning of the 1900s when Hilma was young,” she says. “The invention of the X-ray. The invention of the atom. She drew from all these sources and translated them into her paintings.”

The Paintings for the Temple are alive with this scientific sense of inquiry, along with a deep and abiding wonder. In Primordial Chaos, geometric shapes shoot sparks and rays, while strange words possess multiple meanings, carefully detailed in her notebooks. The Ten Largest cast the smallness of human life against the vastness of infinity, the way you can put your ear to a shell – a recurring shape through these paintings – and hear the sound of the ocean.

In Altarpieces (1915), the final group in the series, tessellated triangles, painted in metal leaf, hold up radiant orbs. The works, she dictates in a 1931 entry, would deliver “a certain power and calm” and should be housed in the temple’s altar room.

In 1908, she showed the paintings to one of her heroes, Rudolph Steiner, an Austrian philosopher and the German leader of the Theosophical Society. He disapproved of her reliance on mediums. For four years, she stopped painting. From the 1920s on, she made incandescent watercolours. An entry from 1932, combines a curious notation with the words ‘All works which should be opened twenty years after my death should carry the sign shown above.’

*

Af Klint’s erasure from art history has become legend, especially during a moment hungry for feminist heroines. She died in a 1944 tram accident. She left her body of work – 1300 paintings, 124 notebooks and over 26,000 handwritten and typed pages – to her nephew Erik af Klint. In the late 1960s, he offered her work to Sweden’s Moderna Museet. They turned it away, claiming that she was more medium than artist. This was ironic given that Kandinsky believed abstraction was a type of religion. Mark Rothko’s painting are considered paths to the sacred. Of course, women who’ve resisted the social order have long been dismissed as heretic or irrational or mad.

For Voss, this is about preserving a hierarchy that, for male artists at least, has been profitable.

“There was Pollock in America and Kandinsky in Europe – the art market had made its prices,” she says. “And then when everything was packaged, Hilma af Klint entered the stage. In a sense, it makes me laugh. It’s like a prank! [The idea] that she’s this crazy, remote woman in Sweden who hit the jackpot of abstraction by chance. That the men were thinking about it and she was just dabbling around.”

Höglund, who is working on plans to preserve and restore the paintings, tells me that af Klint’s work is protected by the Foundation and will remain that way in the future. “Not many are owned by private collectors,” she says. “We have an obligation to take care of her works.”

Dyrschka says that af Klint’s paintings are an antidote to the late capitalist world we’re forced to navigate.

“I think the main question that comes out of her work are ‘What the hell are we doing here? What is the point? Am I here to live eighty years just making money?’”, she laughs. “She came to the answer that there’s more and dedicated her life to this. And to me, this is a very successful life.”

It’s a late capitalist world that’s also polarised, divided by borders and differences and politics. Af Klint spent her life grappling with a society cleaved by gender. She explores the problem of duality in The Swan, no 24, a pair of black-and-white swans painted in 1915, a year into World War I. Their necks and wings are twisted into a larger whole.

“She [brings] in the imagery of the swan, darkness and light, spirit and matter,” says Cramer. “It’s about moving around the oppositions that hold things together – the invisible and the visible, the real and the ideal.”

For Dyrschka, af Klint’s work is a call to self-knowledge, one that is resonant and powerful.

“I think everything in this life is about the right timing and I think it is the right timing for her because human beings are heading in the wrong direction,” she smiles. “They [have] fear, they have anxiety. She was really trying to understand herself. If you know yourself, no one can frighten you ever.”