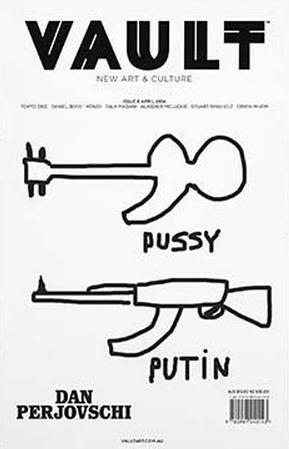

First published in Vault Issue 6, April 2014

For Romanian artist and activist Dan Perjovschi, drawing engenders freedom.

Dan Perjovschi is in the grip of post-travel euphoria. The Romanian artist and activist, best known for covering museum walls with urgent sketches that double as witty political takedowns, has just returned from a week at a little-known, artist-run initiative in the Greek city of Thessaloniki – an exercise that has renewed his belief in the revolutionary possibilities of artistic serendipity.

“Last year, I met a pair of Greek and French artists and they invited me to visit them in Thessaloniki, where they’ve started an artist-run space with some musicians,” he tells me, his grin almost audible over the crackling cross-hemisphere phone connection. “It’s the only art space in that part of Greece and although they don’t have any money because the situation in that country is very tough, they’re not afraid of dreaming big. I went for six days and it was super-good. Sometimes you can have experiences that change your practice and the way you understand it and it’s not always at a big museum or gallery.”

If it seems a little unimaginable that Perjovschi – whose recent career trajectory includes celebrated appearances across some of the art world’s most prominent biennales and audacious drawing installations at MoMA and Tate Modern – could happily scupper worldly reward for the chance to effect change through art, it’s because doing so is his defining missive.

“I don’t associate art with money, glamour or fashion,” he says. “I associate it with knowledge, understanding and ideas, which are essential platforms for contemporary life.”

For Perjovschi, who has spent the last 13 years illustrating Revista 22, a weekly political journal assembled by an insurgent group of writers, philosophers and artists in the wake of the 1989 Romanian Revolution, ideas are both currency and salvation. In 1990, he moved into the art museum in Timișoara, a city that served as the backdrop for the bloody ousting of dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, attacking the walls with a three-day visual diatribe that railed against the homogenising forces of totalitarian rule. He banded with a group of Hungarian colleagues to stage happenings on the outskirts of the city, an act where blindness to the history of performance art worked as a vehicle for transformative impact. And during the 1999 Venice Biennale, Perjovschi covered the floors of the Romanian Pavilion with slogans, wordplay and ideograms that riffed on the contradictions of post-communist life – a move that introduced him to the power of temporality while sealing his place on the international art circuit.

“In Romania, my art education stopped somewhere before Picasso,” laughs Perjovschi, who studied painting at a Soviet-era art academy before trading still lifes for drawing. “But the Venice Biennale was a turning point in my career. I used the floor for my drawings because I was originally supposed to illustrate 100 booklets, but my country didn’t provide the funds in time. I had some markers with me but I didn’t realise that they weren’t permanent. When people stepped on my drawings, they were instantly erased. This possibility excited me. I felt like I was free.”

It’s precisely this invocation of freedom as a catalyst for artistic merit, rather than a by-product of vocational privilege, that causes some critics to dismiss Perjovschi as inauthentic – a kind of Keith Haring lite. In June 2007, the New York Times’ Andrea Mitchell likened What Happened to Us?, a site-specific installation that saw Perjovschi mount a cherry-picker to plaster MoMA’s walls with hastily scrawled observations of US society, as an instance of agitprop – a style of agenda-laden art that elides nuance in favour of simple reductions. But if you look closer, it’s clear that simplicity is exactly the point. A stick figure, when bisected mid-air, shares a perforated upper body with boldly rendered legs, the gaps in its outline mimicking the way the promise of immigration is premised on an erosion of the self. Elsewhere, a moving car crowned with a galleon’s flags foregrounds the neo-colonial quest for oil that drives the war in Iraq while the letters “M” and “E” crushing a diminutive “you” highlight the solipsism at the heart of the country’s popular culture.

“My art is a reduced vocabulary and I like to keep my drawings as simple as possible,” he explains. “Sometimes, I can define my drawings in two words. If you define something in two words, why do you have to draw it? In those cases, I denounce the drawing and make the text.”

To misread Perjovschi’s work is to underestimate how it represents the triumph of expression over form. It also misunderstands how this formlessness allows an artist to stand outside history – a position that’s critical if you want to draw yourself into existence. “When I grew up as an artist in Communist times, there was no market, no private galleries,” he recalls. “I learned how to make money and survive by illustrating a book here, a poster there – I didn’t sell my work, I sold my knowledge. I was not close to the market and built my living outside of it, so I didn’t depend on the market when it finally came to me.”

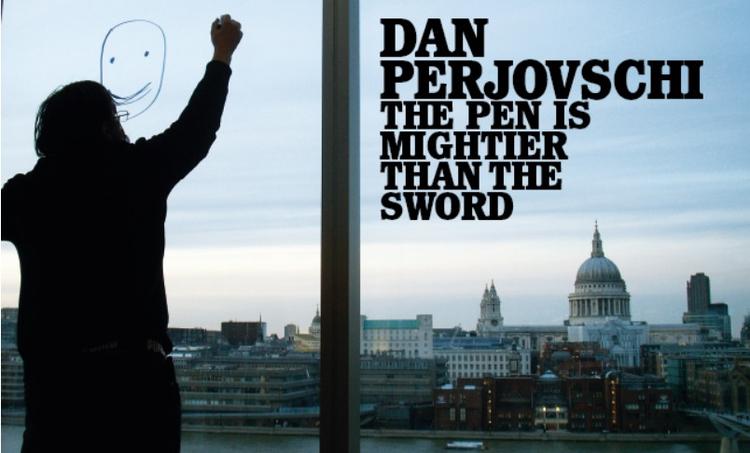

If Perjovschi is disinterested in the market, he’s even more sceptical about its curatorial limitations. He despises art fairs and refuses to make works for gallery display, choosing projects such as White Chalk, Dark Issues (2003), where he transferred his drawings onto the crumbling walls of a Ruhr Valley coking factory, or Japan’s 2013 Aichi Triennale, where consumerist critiques sketched on glass windows proved a striking interruption to city panoramas. And his insistence on obsessively maintaining a notebook is less the act of an artist than it is a journalist – proof of his belief that the value of ideas lie not in permanence but in weightlessness.

“My notebook is my studio – everything I draw on walls, I record here first,” he says. “When I travel to take part in a project, I collect everything I see and hear and when something strikes me when I’m flying across the ocean, it allows me to simply draw it.”

Listening to Perjovschi speak is a lesson in kinetic energy. In his drawings, a segue may show up as a downwards arrow that deflates the “o” in “hope” – an interjection than can move from denoting a country’s singular vision to highlighting the divide between the rich and the poor.

Perjovschi’s dismissal of performance art does nothing to quell the power of movement that is alive in his work – his practice is less installation than it is a visual incantation, a seamless extension of the artist’s world.

“I stopped performance art when it felt too artificial, but a lot of my work is composed of performative drawings,” he says. “Even if you don’t see me drawing, you see my movements in the character of the drawings… It’s a medium that I’ve come to associate with freedom.”

perjovschi.ro

lombard-freid.com