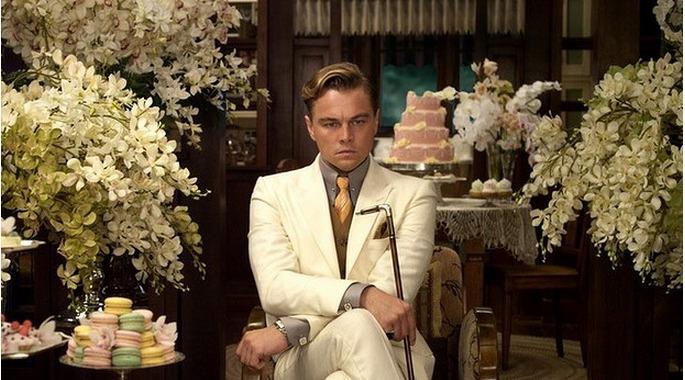

Jay Gatsby is the patron saint of the self-made. The shadowy millionaire may have been shot to death in F Scott Fitzgerald’s taut 1925 masterwork The Great Gatsby but his spectre still appears everywhere from Forbes profiles tracing the rise of entrepreneurs to debates about how minority figures achieve political success. And this month’s $127 million Baz Lurhmann adaptation will see the life and times of the Jazz Age bootlegger rendered in three dimensions and set to a soundtrack by Jay-Z. It’s a fitting tribute to a character whose larger-than-life cultural presence outwits his dubious taste in women or record of personal tragedy.

Unsurprisingly, the last few months has seen Gatsby-mania reach something of a crescendo. The hype surrounding Lurhmann’s remake has turned Fitzgerald’s lesson in the dangers of excess into an aspirational handbook, thanks to a spate of Prohibition-themed parties and breathy editorials on how to turn your suburban two-by-one into an Art Deco lair. And whether or not critics believe that Fitzgerald’s elegant prose is safe with the master of visual hyperbole, there’s a consensus that Gatsby’s pursuit of greatness in 1920s New York is still universally relevant in 2013.

For The New York Times’ Adam Cohen, Gatsby’s cultural pervasiveness stems from his ability to successfully create the life he wants – a goal that’s often linked to the American DreamÔ but easily translates across historical and geographical contexts.

“In the great American tradition of self-invention, Gatsby decided at an early age precisely who he wanted to be. He dropped his father’s clunky, foreign-sounding name, Gatz, in favor of Gatsby, and James for the swankier Jay. A poor runaway from the Midwest, Gatsby has worked his way up to a sprawling Long Island mansion, where he gives boozy, jazz-filled parties for New York high society and drunken flappers. He dresses lavishly, claims to have been born to money and refers to everyone with the upper-crust affectation ”old sport,” he writes.

As the story goes, this didn’t work out so well for Gatsby. But what’s surprising is the way Gatsby’s failures don’t stop us from reading him as a Jazz Age version of modern-day success.

But this isn’t a standalone phenomenon, nor is it limited to fiction. In a February 2013 article in The Atlantic, Alexis C. Madrigal suggests that we construct Great Man narratives by honing in on details that serve as metaphors for genius while glazing over those that hint at a more complex truth. It’s why we’re inclined to cast Don Draper as a Madison Avenue maverick before we dismiss him as an emotionally bankrupt womaniser and the reason Fitzgerald will always be a literary hero, not a man at the wrong end of a battle with alcohol abuse.

Curiously, when it comes to Fitzgerald’s female cohorts, these narratives often work in reverse. For instance, the author’s contemporary Virginia Woolf is often represented as an artist fending off voices in her head rather than the writer of some of this century’s best Modernist prose. And as Daily Life’s Nicole Elphick points out, if maligned writer Cat Marnell trades on her drug use to generate notoriety, it’s a technique that the likes of Brett Easton Ellis has drawn on for years.

In Straight White Male: The Lowest Difficulty Setting There Is, John Scalzi uses a videogame to illustrate how the road to your dreams is made easier or harder depending on the settings you’re assigned. Whether you define greatness as obscene wealth, career success or an artistic legacy, he believes that this is process is smoothest if you’re straight, male and white. For Scalzi, the default barriers for completion of quests are lower and your leveling-up thresholds come fast.

“You automatically gain entry to some parts of the map that others have to work for. The game is easier to play, automatically, and when you need help, by default it’s easier to get.”

But the real trouble with The Great Gatsby is the way we still see it as a universal story of self-invention rather than a singular account of one man’s path. By conflating greatness with male privilege, we lend ironic new meaning to the novel’s famous last words: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”