Zaha Hadid, the Pritzker-prize winning force who died suddenly, aged 65, earlier this year was one of architecture’s most polarising figures, her curvaceous buildings – symbolic of possibilities rather than boundaries – proof of a vernacular that exploded the Modernist obsession with hard lines and right angles and pushed the field to its very edge. As Melbourne gets a step closer to its own Zaha Hadid building (a 54-storey tower, designed to resemble a series of stacked vases), Vault asked three acclaimed voices in Australian architecture to choose their favourite Hadid project and reflect on the ways they’ve been influenced by her life and work.

Karl Fender: Vitra Fire Station, Germany

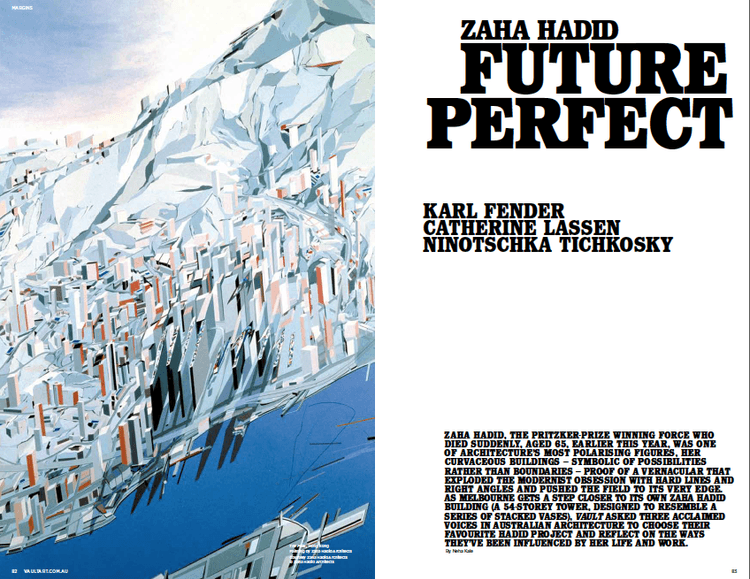

The larger-than-life, Suprematist landscapes that Zaha Hadid painted in her early career captured the architecture industry’s collective imagination, hinting at what the built world could look like in the future. But when Hadid’s iconic Vitra Fire Station was completed in Weil Am Rhein, Germany in 1993, the sense of intellectual curiosity and architectural expression that was a hallmark of her paintings were physically realised for the first time.

Although modest in scale, the building soared in spirit and presence. It harnessed the exuberance of her paintings and elevated the practical fire station paradigm into the realm of sculpture. The notion of a fire station as a box equipped with tilt-up doors and fire-fighting appliances was recast as an artful composition of dramatic planes and surfaces.

Hadid was committed to exploring and expressing the emotive qualities of her architectural language and displayed a resolute confidence in her craft. In many ways, her paintings were two-dimensional explorations, which surprised the world by transcending the boundaries and strictures of architectural thinking and documentation. This allowed her to foster a singular oeuvre and leave the world a rich legacy indeed.

Karl Fender is a founding director of Fender Katsalidis, the architecture firm behind the Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart, Canberra’s New Acton precinct and Australia 108 in Melbourne’s Southbank.

fkaustralia.com

Catherine Lassen: The Peak, Hong Kong

In a public lecture at the Sydney Opera House in the 1980s, Hadid presented radically beautiful architectural paintings for The Peak, her winning competition entry for a private leisure club in Hong Kong. An architecture student at the time, I was struck by the precision and layered thought within her unexpected visualisations. Her planes of colour seemed to dissolve and fragment both the towered metropolis of Hong Kong and its dramatic surrounding landscape into slivers of paint and light, which floated in space to re-form as an intense, inhabited moment. Although her paint was materially emphasised, the suggested building evoked immaterial conditions.

Perspectives of this project indicated multiple dynamic viewpoints, frozen moments from a place hard to locate, perhaps from somewhere in the future. Clearly experimental in conception, the work seemed to be searching for possible new ways forward, but from within modernism, pursuing elements such as Russian Constructivism and Suprematism.

Hadid’s contribution was wide-ranging. I saw her teach at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design with a generous open-mindedness, intellectual intensity and a lack of pretention. Her installations, such as The Great Utopia exhibition at the Guggenheim in 1992 were architecturally energetic and provocative. She led knowledgably, with commitment and was never afraid to take chances.

Catherine Lassen is an architect and Senior Lecturer in Architecture at the University of Sydney and recently designed site-specific furniture pieces for works by Yoko Ono as part of a major MCA retrospective on the artist’s work.

Ninotschka Tichkosky: Kartal Urban Transformation Project, Istanbul

Although Zaha Hadid’s reputation has been largely built on architecture’s object-based nature, her attempts to rethink city-making, as illustrated by her masterplan for the Kartal Urban Transformation Project, is one of her most interesting achievements. Cities are a unifying platform for architecture in urban areas and considering new possibilities for the way we shape our cities is critical to our work.

The Kartal project explores the use of computational scripting to inform urban street and block patterns, connections as well as a more fluid approach to density and height. It changes the conversation we might have about future city planning and urban renewal. Although the success of this masterplan was unproven, its relevance lies in the concepts Hadid raises. The soft grid adjusts itself to Istanbul’s future conditions while drawing on the city’s historical plan — a radical departure from more typical, static urban frameworks. When we think about innovation precincts and smart cities, it’s so important to consider new paradigms.

Zaha Hadid has often been accused of championing siteless architecture but when [BVN Architecture] collaborated with Zaha Hadid Architects over the proposed redevelopment of Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station, as part of the Flinders Street Station Design Competition in 2013, we were absolutely focused on knitting the project into the existing urban space. There was often a lack of understanding about her projects’ intentions. It’s also important to acknowledge that, despite Zaha’s strong personal brand, Zaha Hadid Architects is a large firm and many hands contribute to her portfolio of work. Despite the tension between her believers and non-believers, Hadid was a highly talented and formidable person who managed to grow her practice and continue to explore the limits of our profession. We should be grateful for this alone.

Ninotschka Tichosky is an award-winning principal of BVN Architecture and counts Sydney’s ANZ Stadium and the proposed redevelopment of Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station – a collaboration with Zaha Hadid Architects – among her projects.