First published in BROAD magazine, March 2017.

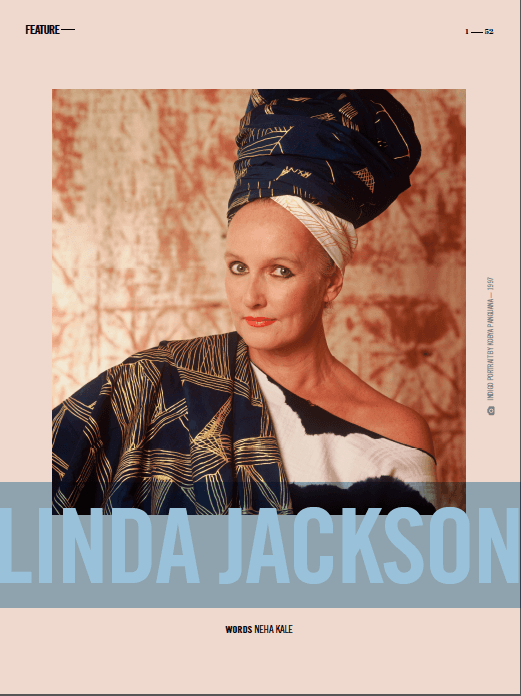

Linda Jackson can see into the future. Although the iconic artist and fashion designer, who made a generation fall in love with the dazzling shades and dramatic shapes of the Australian landscape, came of age decades before we trawled Instagram for inspiration, she’s long believed that the images we look at help us get to know the world.

“I’ve always connected with my surroundings through the visual and Instagram proves to me that the volume of pictures and colours out there is endless,” says Jackson, who updates her own feed — a mix of vintage photos and works-in-progress — every few days. “If you love colours, artworks and paintings, you can discover a world of artistic people, doing amazing things. It makes me ask myself: what would I be doing today if I was a young person? It’s really interesting.”

It’s hard to imagine that Jackson, who I’m chatting with at a café outside the Wollongong Art Gallery on the last day of Hand and Heart Shall Never Part, an exhibition based on her collaborations with her friend, the late artist and gay activist David McDiarmid, could lament the paths she might have missed. Along with her designs for the Flamingo Park Frock Shop, the Sydney boutique that was founded by kindred spirit Jenny Kee and went on to define the ‘seventies zeitgeist, she’s spent the last four decades working across fashion, art, photography and theatre. Her expressiveness shows. The forty-degree heat is a recipe for wardrobe blunders but in a felt fedora, floral-print shirt and her cat-eye glasses, Jackson, is radiant and composed — despite driving down to Wollongong from Brisbane, where she’s been painting costumes for Cargo Club, a new production by the Cairns-based Centre for Australasian Theatre. “Well, look, you just get really busy,” beams Jackson, who’ll soon head back to Bendigo where she spends part of the year looking after mother, “and you just don’t realise it until you stop.”

**

Jackson was born in 1950 and raised in Beaumaris, a seaside suburb of Melbourne. Her parents were former ballroom dancers who took her on camping trips with her cousins and encouraged her creative impulses. “I took calisthenics so there was always a lot of dressing up and because my dad was a printer, I had access to paper,” she grins. “I read National Geographic when I was little and Vogue Italia because Melbourne back then had great bookshops! We’d meet family in the bush. It was normal for me to be sleeping under the stars.”

Jackson studied fashion at Melbourne’s Emily Macpherson College and enrolled in a photography course before traveling to Asia in the late sixties with the designer Peter Tully and the photographer Fran Moore. This journey, which criss-crossed New Guinea and Indonesia and culminated in London and Paris via Istanbul and Amsterdam, galvanised Jackson’s ambitions. “I studied the way women dressed in a lot of countries, how they made their own clothes and textiles and it filled me with great joy,” she says, eyes shining. “Travelling was my university of life.”

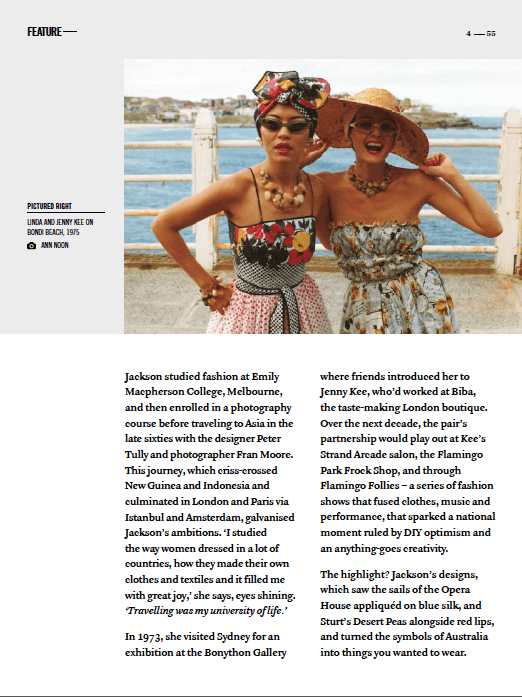

In 1973, she visited Sydney for an exhibition at the Benython Gallery where friends introduced her to Jenny Kee, who’d worked at Biba, the taste-making London boutique. Over the next decade, the pair’s partnership would play out at Kee’s Strand Arcade salon, the Flamingo Park Frock Shop and through Flamingo Follies, a series of fashion shows that fused clothes, music and performance art and sparked a national moment ruled by DIY optimism and an anything-goes creativity. The highlight? Jackson’s designs, which saw the sails of the Opera House appliquéd on blue silk and Sturt’s Desert Peas alongside red lips and turned the symbols of Australia into things you wanted to wear.

“Jenny and I had come back to Australia and travelled the world in different directions, it was the universe’s plan that we would meet and we haven’t stopped talking since,” says Jackson, whose phone rings halfway through our conversation and — surprise! — Kee’s on the line. “We spent a year planning each show, Jenny had seen so many venues and I was mad about Martha Graham, performance and dance. The first was at a Chinese restaurant because we’d pick up my frocks in Bondi and have yum cha in Chinatown. Our last one, Flaming Opal Follies was in a nightclub. Everyone worshipped London and Paris but we were inspired by Australia and could never understand why it was unusual that we were looking to our own country. People were trying to put us into boxes – but it was fashion and art, we dressed each other and some people laughed because the colours were too bright. We loved it! We didn’t believe in categories.” She dissolves into giggles. “Now it’s like you’re married, you’re not married, you’re gay, you’re straight. Everything’s back in the filing cabinet!”

***

Jackson, who ran her own labels Bush Couture and Bush Kids from 1982 to 1992, is back in the spotlight thanks to her 2012 retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria, Flamingo Park and Beyond at the Bendigo’s Living Art Space and the new show in Wollongong. But more remarkable is the way her nomadic instincts and category-defying output have gathered steam over time. After she shuttered her own studio in the nineties, Jackson relocated to Arnhem Land, working closely with Indigenous women painters and going on to collaborate on silk scarves with artists at Mossman Gorge in Queensland. (An upcoming show at the Art Gallery of South Australia features textiles produced in partnership with artists at Utopia Station.) Then there’s her theatre work and three-season collaboration with cult label Romance Was Born (“I write letters but with Romance, I had to learn how to text!”) As if that isn’t enough, she tells me that she’s looking forward to having time to paint and work on her dream project — a children’s book based on her own adventures. “I’ve always wanted it to be a Disney cartoon. I did have some meetings with Disney and they said it was fabulous but I need to work on the characters,” she laughs. How fitting that the girl who saw the world in pictures might inspire a new generation to see it that way, too.